Anjali Reddy (‘18) is currently the Editor-in-Chief of the Webb Canyon Chronicle and has written for the paper since her freshman year. She started...

Cardi B is one of Hip Hop’s biggest feminist icons to date. She, along with other rappers have worked to dismantle the misogyny typically associated with their field. Graphic Courtesy of VH1.com

May 23, 2018

There is no question that Hip Hop is powerful. It’s an entire genre that unites and shares stories in a way unlike any other music genre, where anyone can make it and everyone’s stories matters. Hip Hop’s influence is most evident in the way we speak, dress, or connect with people. In many ways Hip Hop has been a voice of hope and justice in our society, rappers serving as political activists with charged lyrics about what is right and what is wrong.

Still, the question remains- how can such a progressive and modern form of music still take on the role of misogyny and objectification and as women how do we deal with it?

For me personally, I had not even paused to consider the implication of being a woman who enjoys rap until very recently.

A few months ago, my brother and I were driving home, and on this particular night, we had a rap playlist on shuffle. I enthusiastically rapped along as each song played, and as I shuffled through each of the songs on my playlist, I noticed almost all of the lyrics were objectifying, disrespectful, and incredibly aggressive towards women. Most of the rappers themselves were abusive, and I could not understand as to how I had ignored this fact for the last 18 years of my life because the music was good, catchy, or whatever excuse I could argue. However, all the female rappers on my playlist such as Cardi B, Nicki Minaj, and Beyonce were still really empowering. Should I only be listening to them?

Thus, my identity crisis began. As a self-proclaimed feminist who is all for women’s rights, how could I continue to listen to my music without becoming a complete hypocrite? I didn’t want to support these men or their lyrics, but I was still a sucker for good music. What was good music?

Being a fan of hip-hop is a gray area when it comes to deciding what is worth supporting and what is not. Hip Hop generally originates from a lifestyle rooted in a lack of opportunities and in urban areas, creating problems for communities such as gang violence, drug trade, and domestic violence.

A byproduct of those situations is sexual abuse, rape and the objectification of women. For many of these artists, this is just the life they’re used to. However, Hip-Hop feminism is changing the way we look at Hip-Hop, and what it’s been stereotyped as before. There is a reason it had so much misogyny in its past.

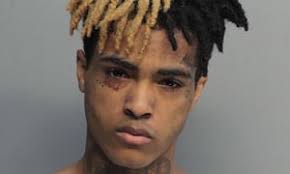

Last year, famous rapper XXXtentacion was charged with aggravated battery of a pregnant woman, domestic battery by strangulation, false imprisonment and witness tampering. However he still remains one of the top chart rappers to date. Graphic courtesy of the Guardian.

It is no secret that the world of rap and hip-hop is revered for its emotion, wittiness, and soul in its lyrics. However, it is a well-known fact brought up by countless magazine articles that the majority of rap lyrics are misogynistic. Rappers who are charged with domestic violence top the charts in hundreds of countries, and the majority of media coverage surrounds the success of their music.

The most pointed example of our acceptance of such immoral actions is embodied through one of Americas trendiest rappers: XXXTentacion. “I’ma f*** ya’ll little sisters in they throats. I swear to God anybody that called me a domestic abuser, I’ma domestically abuse your little sister.” So says XXXTentacion in an Instagram rant, responding to his domestic charge allegations. This is not the first time the rapper, born Jahseh Onfrey, has dabbled with violence in his short 19 years.

Last year, Onfrey was charged with aggravated battery of a pregnant woman, domestic battery by strangulation, false imprisonment and witness tampering. He pleaded not guilty, and his trial, due to be held on the 5 October, has just been postponed – with no set rescheduled date. In the year since Onfrey was charged, he has soared to the top of the charts; his album reaching number two in the US charts and number 12 in the UK charts.

However, in this time Onfrey’s music has only flourished. While Onfrey’s alleged victim speaks in detail about the routine violence she experienced, Onfrey is free to threaten her on national social media, with no repercussions from the media industry. He is lauded as the ‘‘Rapper we need to know about’”, with his songs raking up to 75 million views on YouTube.

There was very little coverage a few weeks ago of the alleged victim giving evidence in court, but more focus on Onfrey’s success with his new album. We place more focus on his music than we do on his history as an abuser. And sadly, this isn’t an isolated case. There seems to be a trend of disregarding ethics, which could potentially go back to the original environment rap and hip-hop was founded in (Weitzer). This trend can be seen through the plethora of stories of rappers in the news committing unethical crimes.

Another instance in which the public places more focus on a rappers musical success over their moral obligation is in the instance of R. Kelly. R Kelly is still widely acquitted and it seems many seem quick to forget R Kelly’s quickly annulled marriage to then 15 year old Aaliyah (he was 27). Kelly was and still is a predator. He was acquitted on 14 counts of child pornography back in 2008 and it was only recently that news emerged of the singer’s ‘sex cult’. Despite this, his songs are still played at family weddings and at the end of mediocre student nights and no one seems to blink twice. These stories of Kelly are normalized by the media, in favor of covering his topchart songs.

Kelly continues to make music with Justin Bieber, Jhene Aiko, and Chance the Rapper – which is interesting as almost none of their lyrics or histories revolve around abusing women. Why Is the industry failing to challenge rappers like Kelly and Chapelle?

From Chris Brown, to Woody Allen, to Mel Gibson, to Casey Affleck, men in the public sphere always get away with abusing women. They get little societal scolding because their “talent” supersedes judgement. While the men are praised in the public sphere, their victims are often accused of lying and exaggerating. We routinely ignore the voices of women, especially black women, when they come forward to talk about sexual violence. When we do this in such a public light, what message are we giving to men? Essentially, it is this: all will be forgiven (Morgan).

However, what is more worrisome is that as a misogynistic society, we are ingraining the concept that disrespectful lyrics are what frame success. Why is it that notable “nice guy” rappers like Drake and Kanye West also have explicit raps? Kanye and Drake have heavily problematic lyrics and themes in their songs. And, they are very popular with women. Men and women have to demand more from our artists. We cannot let misogyny slide just because we like a rapper’s personality. When we support them we are endorsing their misogyny. Why is hip hop still lagging behind on the feminist front?

In Colonize This, “Love Feminism but Where’s My Hip Hop,” by Gwendolyn D. Pough, speaks to the masculine spaces of rap and how for rappers lyrics, “let them know they could have a voice.” Pough speaks of how as a female rapper, rap allowed, “a strong public presence that allowed (me) to rap about issues.” Through her explanation of why people use rap as an outlet or medium of expression, the author begins to question the lyrics and connected identities of several rap songs with lyrics applauding acts anti the “feminist identity.” Pough writes, “Young women growing up today are not privy to the same kind of pro-woman rap I listened to via Salt-n-Pepa.” Pough argues that although sexism exists in rap music, it also exists in America. “Rap music is not produced in a cultural and political vacuum.” Misogyny in music will not end until misogyny in society does (Pough.)

As more and more rap gets slammed for being sexist, research into other music genres has started to take place. Rap music has a reputation for being misogynistic, but surprisingly little research has systematically investigated this dimension of the music. R. Weitzer conducted a study that assessed the portrayal of women in a representative sample of 403 rap songs. A content and lyrical analysis identified five gender-related themes in this body of music—themes that contain messages regarding ‘‘essential’’ male and female characteristics and that espouse a set of conduct norms for men and women. This analysis situates rap music within the context of larger cultural and music industry norms and the local, neighborhood conditions that inspired this music in the first place. Its content analyzes the subversive prevalence of rap in our culture, and its effects on both adolescent men and women. There is an obvious relationship between art and society. Art not only mirrors and amplifies social norms, but it also influences society while being a product of society. Essentially, art and society influence each other in once vicious cycle. Even nice-guy rappers such as Drake will rap about the exploitation of women (Weitzer).

Another study conducted by a researcher at Michigan University revealed that Rap and hip-hop get much more attention in popular media for being sexist than do genres such as country and rock. Six genres used were rap, hip-hop, country, rock, alternative, and dance. The five themes used are portrayal of women in traditional gender roles, portrayal of women as inferior to men, portrayal of women as objects, portrayal of women as stereotypes, and portrayal of violence against women. Each instance of sexism is also classified as benevolent, ambivalent, or hostile sexism. She then used the results to determine whether or not other genres are as sexist as hip-hop and rap. Possible reasons for differing levels of sexism as well as potential social implications of sexism in music again, go back to what the crowd wants (Neff). It seems that it is generally accepted that although lyrics in rap are incredible disrespectful, it is the job of the listeners to separate the art from the artist. Hip Hop’s Misogyny Problem Keeps Getting Worse, Konder argues that men are entertainers. Their purpose is to produce art, not be role models. Still it’s only natural that their followers look up to them. Conversely, this cult-like following enables the artists to engage in further acts of sexual harassment, domestic violence, and rape. Their rise on the charts only reinforces the wider problem of misogyny and rape culture. It also diminishes hope for any help that these victims may receive. However, she brings up the point that, “Although they are simply entertainers, everyone should be held to the standard of being a good human. They floss their possessions: money, cars, clothes… and women. They have everything a boy could ever want. But a human is not property, regardless of gender.” (Konder).

As centuries go on, the world is constantly evolving to better itself and the individuals in it. Feminist theory, no matter the time period, exists to expose all the ways that our governmental institutions such as laws, businesses, and education perpetuate sexism. Although they all differ in their treatment and views of the system, as the three waves of feminism have evolved, the system itself has also adapted its existence in response to the three waves (Peoples).

As females, we are taught by society and the media, that good-mannered girls apologize. “Sorry” had become a bad habit that slipped out of our mouths before we could stop it. This so-called harmless word had subtly changed not only how we are perceived, but how we understand ourselves. In Amy Poehler’s book, Yes Please, she wrote an entire chapter on apologies, and explained that “it takes years as a woman to unlearn what you have been taught to be sorry for.” However, female rappers have tried to reclaim their music by empowering women. Feminist rappers like Queen Latifah, Yo Yo, and Roxanne, speak their minds on issues that truly matter, but this isn’t unusual in pop culture. Queen Latifah’s rap surrounds the idea of women promoting other women and makes explicit assertions of female strength.

“It’s not a black and white issue in terms of feminism and how it relates to hip-hop.”

When Dr. Cantwell, a humanities teacher at the Webb school was asked about her thoughts surrounding feminism and hip-hop, she offered the insightful advice that it’s not a black and white issue in terms of feminism and how it relates to hip-hop. Female rappers have positive messages for women, however, there’s always been a longstanding tradition of sexualizing women which can be seen through music videos. There’s no concrete definition of what a feminist is. Like rap music does not make you a bad person. There is no such thing as a “bad feminist.”

“One thing our culture is dealing with right now is although it may seem like the line between deciding if someone is good or bad is concrete, it is in fact quite blurred. If you start ruling out artists who have issues in their personal lives and face allegations, no artists are going to be left.”

What’s dangerous in our culture is thinking it is ok to judge people based on what they like or don’t like. It is extremely negative to judge each other on what they feel comfortable with when it comes to music, especially because it is such a personal preference.

It’s important when analyzing this type of music to not draw a connection between lyrical statements and the personal views of an artist or the listener. Oftentimes a tough persona is just that — a persona — so when is a sexist message ironic or subversive, and when it is a hateful call to action?

One could argue that feminists have a duty to continue to listen to Hip-Hop and participate in Hip-Hop culture, acknowledging its misogyny while building up equality. After all, it’s not only one’s responsibility to preserve the culture you love, but to make it better.

We need more female, commercially successful voices in hip-hop. The generation of fierce, empowered femcees of the late 80’s and early 90’s (Queen Latifah, MC Lyte, and Queen Lauryn herself) can be born again. It’s becoming more evident through female rappers such as Cardi B and Nicki Minaj that being unapologetically yourself is important now more than ever for the female consciousness. However, although female rappers are starting to become more popular, I look forward to the day there is an even amount. We need more female voices in hip-hop, making catchy songs about their own experiences. We need to bop our own truths, and then we may finally be able to honestly don the labels of both feminists and hip-hop fans.

Konder, K. (2017). Hip Hop’s Misogyny Problem Keeps Getting Worse. Mass Appeal.

Peoples, Whitney A. “‘Under Construction’: Identifying Foundations of Hip-Hop Feminism and Exploring Bridges between Black Second-Wave and Hip-Hop Feminisms.” Meridians, vol. 8, no. 1, 2008, pp. 19–52. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40338910.

Radford‐Hill, Sheila. “Keepin’ It Real: A Generational Commentary on Kimberly Springer’s ‘Third Wave Black Feminism?’” Signs, vol. 27, no. 4, 2002, pp. 1083–1190. JSTOR

Wetizer, R. (2009). Misogyny in Rap Music. SageJournals

Roberts, Robin (1994). Queen Latifah’s Afrocentric Feminist Music Video. African American Review, Vol 28. Black Women’s Culture Issue.

Donnelly, Mike. “Hip-Hop Music and Gender Stereotypes: A Semiotic Analysis of Masculinity in Hip Hop.” 28, April 2010. http://prezi.com/gdgef4rrjfir/hip-hop-and-gender-stereotypes/

Morgado, Marcia. “The Semiotics of Extraordinary Dress: A Structural Analysis and Interpretation of Hip-Hop Style.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 25.2 (2007): 131-155.

Nielson, Erik. “‘Can’t C Me’: Surveillance and Rap Music.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 40, no. 6, 2010, pp. 1254–1274. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25704086

Roberts, George W. “Brother to Brother: African American Modes of Relating Among Men.” Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Jun., 1994): pp. 379-390. Web.

Thompson, George D. “Cultural Capital And Accounting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 12.4 (n.d.): 394-412. SocINDEX with Full Text. Web.

Thompson, George D. “Cultural Capital And Accounting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 12.4 (n.d.): 394-412. SocINDEX with Full Text. Web.

McCabe, Shannon. “PQDT Open.” Pqdtopen.proquest.com. N.p., 2018. Web. 23 Jan. 2018.

Sewell, Amanda. “PQDT Open.” Pqdtopen.proquest.com. N.p., 2018. Web. 23 Jan. 2018.

Viega, Michael. “PQDT Open.” Pqdtopen.proquest.com. N.p., 2018. Web. 22 Jan. 2018.

Vito, Christopher. “PQDT Open.” Pqdtopen.proquest.com. N.p., 2018. Web. 23 Jan. 2018.

Moraga, C. (2010). Colonize This!. Berkeley, Calif.: Seal Press.

Morgan, Joan. “Fly-Girls, Bitches, and Hoes: Notes of a Hip-Hop Feminist.” Social Text, no. 45, 1995, pp. 151–157. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/466678.

Roberts, Robin (1994). Queen Latifah’s Afrocentric Feminist Music Video. African American Review, Vol 28. Black Women’s Culture Issue.

Anjali Reddy (‘18) is currently the Editor-in-Chief of the Webb Canyon Chronicle and has written for the paper since her freshman year. She started...