Cathy Yan (‘19) is a senior boarding student from Beijing, China. She calls Beijing home, but has also lived in Canada and the United States. Although...

May 30, 2019

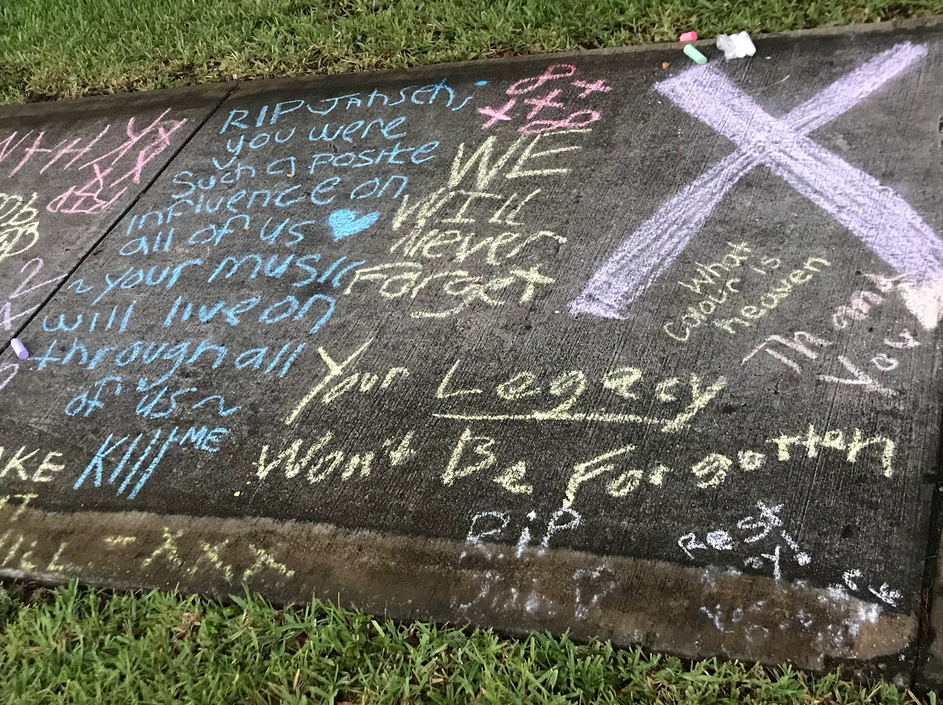

A memorial to XXX Tentacion is scrawled in chalk on the sidewalk. Picture taken from Wikimedia Commons.

“Hip-hop’s emergence drew the attention of people outside the urban neighborhoods where it arose, and during the 1980s and 1990s, the recording industry turned hip-hop into big business.” – Michael P. Jeffries “Thug Life”

Hip-hop originated in urban black and Latin American neighborhoods experiencing poverty in the 1970s, most notably, the South Bronx in New York City (Britannica). Many city residents like those in Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia found themselves jobless in the face of deindustrialization because companies started moving low-skill manufacturing jobs to countries like India where labor was cheaper (Oware).

Unemployment, declining social services and rising crime rates plunged these urban communities into poverty (Oware). Hip-hop was created as a way to express frustrations about the lack of education and job opportunities for inner-city minority communities. The genre found its footing in American culture live – DJs, MCs, rappers, and break dancers used their streets as a stage to speak out about the economic injustice they experienced (Jeffries 1).

Consequently, common themes in hip-hop are nihilism about the future and ongoing violence (Kubrin 441). Scholars researching inner-city culture in relation to rap music commonly identify that “young people bereft of hope for the future have made their peace with death and talk about planning their own funerals…The high death rate among their peers keeps many from expecting to live beyond age twenty-five” (Anderson 135).

However, “hip-hop’s emergence drew the attention of people outside the urban neighborhoods where it arose, and during the 1980s and 1990s, the recording industry turned hip-hop into big business” (Jeffries 1). Today, hip-hop has grown beyond racial and experiential boundaries. The market is currently worth over 10 billion dollars and hip-hop makes up 31% of the total revenue generated by the music industry (Watson) (Wang).

Currently, four major record labels – Sony Music Entertainment, Electric & Musical Industries Limited, Universal Music Group, and Warner Music Group – control 86% of the industry by having smaller, independent labels as subsidiaries (Jeffries 3). Hip-hop’s popularity spread outside of the communities that created them and changed to become a genre that glorifies money, drugs, and violence.

Prior to 1988, research identified that lyrics about “residence (place), partying, romance, humor, and parody” dominated rap. However, after 1988, rap lyrics predominantly referenced “pimping, hustling, sex, violence, materialism, and homophobia” (Oware). This change was largely caused by the commodification of hip-hop after mainstream labels identified the genre as popular enough to be profitable.

Large record labels began by collaborating with independent labels by manufacturing and distributing their records (Oware). The 1996 Telecommunications Act “lifted the national cap on radio station ownership”, allowing companies like Clear Channel Communications to own 1,238 radio stations (McCabe) (Oware). The legislation contributed to the increasing control large labels had over hip-hop because the songs played on the radio were determined solely by corporations rather than locals.

Rap and hip-hop music began evolving to suit the growing young white audience. Companies valuing profitability over authenticity “began buying out independent labels and began signing their own artists” to appeal to the new demand. The saturation of rap with hypermasculinity was “encouraged by corporate entities” (Oware). The now predominantly white audience had little regard the social issues hip-hop grew from. Instead, white youths were attracted to the “image of an impoverished, young and violently “foul-mouthed” black male who espouses criminal activity” (Oware). In a comprehensive study done by Jennifer Lena in 2006 on the “Social Context and Musical Content of Rap Music”, she found that major labels produced five and a half times more “ghettocentric” rap singles than all independent labels combined between 1979 and 1995 (Lena).

Underground hip-hop developed alongside the mainstream. Although the exact definition of “underground hip-hop” is widely debated by fans, critics and academia, the term generally refers to artists signed to independent labels, self-made groups and/or using their own methods of distribution such as SoundCloud, YouTube and CDs. The sub-genre first defined itself with lyrics against the “commercial motivations and corporate interests governing its perceptions of good music” (Oware).

However, underground artists also imitate mainstream rap styles in order to gain commercial success. “Predominant topics among popular or successful underground rappers include misogyny and hypermasculinity” (Oware) because those lyrics had greater appeal to mainstream listeners. The most recent breakthrough of underground rap came from the platform SoundCloud, which allows artists to upload their own music to millions of listeners.

Currently, popular hip-hop and rap music is saturated with SoundCloud rappers. Online publications began to emerge with headlines like “How Rap’s SoundCloud Generation Changed the Music Business Forever” and “How SoundCloud Rap Took Over Everything”. GQ Magazine described SoundCloud Rap as a “DIY teen hip-hop genre” (Battan).

Major labels quickly jumped on the explosive growth of new artists like Juice Wrld, XXXtentacion, Tekashi 6ix9ine, Lil Peep and Lil Pump. Like many of these artists, Juice Wrld “went from being just another kid posting songs on SoundCloud to a major-label obsession” (Battan). Interscope Records, a music label owned by Universal Music Group, offered him a 3-million-dollar record deal in early March of 2018 (Stutz). In the fall of 2018, his album with Future Future & Juice WRLD Present…WRLD on Drugs debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard 200 (Garvey).

The sub-genre’s success can be attributed to its relatability to teens consuming the majority of rap and hip-hop music. A popular subgenre of SoundCloud rap is “emo rap” and the terms are sometimes synonymous with each other. Teen rappers pour their emotions over a beat the same way artists during the 2000s emo rock era did (Beausoleil). The first track of XXXtentacion’s album 17 demonstrates the genre well. He says, “if you are not willing to accept my emotion, and hear my words fully, do not listen” (Genius).

These rappers tapped into the same nihilistic themes present in hip-hop since its creation but made it more relatable to young audiences by associating their struggles with love, drugs and anger. Like their predecessors, SoundCloud rappers’ lyrics are expectant and even at times welcoming of death.

Lil Peep was born into a middle class white neighborhood in Long Island, New York (IMDb). His parents were both Harvard graduates and he had good grades in high school (IMDb). However, he was diagnosed with depression early on in life. He dropped out of high school to finish his diploma online and thus began making music (Madden). He grew up on pop-punk and emo rock (Madden). His early musical influences combined with the soaring popularity of hip-hop during his late teenage years leave a clear mark on the songs he uploaded to SoundCloud. Lil Peep is an example of the adaptation of hip-hop to different circumstances whilst maintaining the genre’s original themes.

With song titles like “Better Off Dying”, Lil Peep is an emblem of sad boy culture. He raps in a pained voice “Cocaine lined up, secrets that I’m hidin’/ You don’t wanna find out, better off lying / You don’t wanna cry now, better off dying” (Genius). His lyrics describe using cocaine as a way to self-medicate and express feelings of hopelessness about getting help. He also features of fellow rapper Cold Heart’s song “Dying”, whose last line is “A lot of people have seen their friends die, I don’t want anyone to see any of their friends die anymore” (Genius). This lyric speaks again to the reality of the high death rates among their peers that also translate to an expectant attitude towards the idea of an early death in rappers (Anderson 135).

Tragically, Lil Peep died on November 15th, 2017. He overdosed on the fentanyl laced Xanax he posted himself swallowing on Instagram just hours before his death. His death was widely covered and glorified by the media and as a result, his music streams dramatically increased.

The emergence of the mythical ’27 Club’ is a demonstration of prevalence and glorification of death in the music industry. The term ’27 Club’ originated after Kurt Cobain’s death in 1994 at the age of 27, the same age as Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Brian Jones and Jimi Hendrix (Rolling Stone). Although the term stems from rock & roll and not rap, fans have applied the term to the deaths of Tupac Shakur, The Notorious B.I.G. and Lil Peep. Later, the term was also used with XXXtentacion, and Mac Miller.

XXXtentacion rose to fame on the same platform as Lil Peep and Juice Wrld. His song “Look At Me” skyrocketed X’s name into the mainstream and peaked at No. 34 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2017 (Billboard Staff). Shortly after, X signed a record deal with Bad Vibes Forever/Empire which is a subsidiary of Empire Distribution (Sisario) (Shifferaw). His album 17 debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard 200 (Shifferaw). He then signed a 6 million dollar deal with Caroline, a subsidiary of Capitol Music Group and released his second album, ? (Shifferaw). “Sad,” a song from the album, reached No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100 (Billboard Staff). In 2018, he signed a 10-million-dollar deal with Empire Distribution, a distribution unit of Universal Music Group.

Just weeks after the record deal and two months after X announced his upcoming album Skins, X was shot and killed in an armed robbery outside a motorsports store in Florida (Sisario). X was 20 years old. Artists like Kanye West, Joey Bada$$, and Lil Xan took to social media to express their condolences (Weatherby). His large and loyal fanbase was devastated. They quickly made the connection between X’s early death to Lil Peep’s and dubbed him a member of the 27 Club. Juice Wrld even recognized fans’ comparisons in his song “Legends”, released the day after X was pronounced dead (Mojica). The song’s lyrics go, “Sorry truth, dying young, demon youth / What’s the 27 Club? / We ain’t making it past 21” (Genuis). This lyric again references the nihilism rappers of the current generation continue to face about their futures.

Lil Peep and XXXtentacion’s fame means media companies quickly capitalized on their deaths. The resulting publicity benefited their posthumous careers and their respective record labels. After Lil Peep’s death, music producer George Astasio and Peep’s friend and collaborator Smokeasac went through the contents left on his laptop (Caramancia). There were finished songs and fragments of songs that have not been released to the public (Caramancia). After numerous emotional sessions, Smokeasac and Astasio finished Come Over When You’re Sober Pt. 2 and it was released in November of 2018 (Caramancia).

However, before his death, Peep worked independently. He made his SoundCloud uploads in his room on his laptop. “Lil Peep had taken an independent route to stardom” (Battan) and much of his work after he signed to Columbia Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment, was produced the same way. Peep did not have concrete plans for the Pt. 2 album and according to those that listened to the contents of his album, “Peep was growing in different directions, and much of that music is still unheard” (Caramancia). An example of the change in direction is the bonus track “Sunlight on Your Skin”, which is noticeably more upbeat than his previous songs and void of references to drugs and death.

Instead, the album was based off of Peep’s previous work. As a result, the pained songs like “Leanin’” on Come Over When You’re Sober Pt.2, although authentic to his established work, seems insensitive in the wake of Peep’s overdose. In doing so, the record label profits and Peep’s final songs showing his personal growth were disregarded to fit a corporate model that generated profit.

X’s legacy is even more tumultuous than Peep’s. After X’s death, his unfinished vocals were worked into his posthumous album Skins, perhaps with less sentimentality than Peep’s album. He also had unfinished designs for his clothing line Bad Vibes Forever. Both of the posthumous projects were finished by X’s friends and team (Rudas). Although these people arguably know the rapper best, the projects are not fully representative of the rapper. If his legacy lives on through his music, then his legacy has indefinitely been shaped by other people and his estate reaps all of the monetary benefits.

‘Skins’ debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard top 200 charts despite the unfinished vocals and added features to X’s songs (Caulfield). His other songs like ‘Sad!’ became a posthumous No. 1 single for the first time since The Notorious B.I.G.’s ‘Mo Money Mo Problems’ in 1997 (Giuloine). According to the New York Times, his audio and video streams total 4.6 billion (Sicario). Being a rapper with lyrics like “I control my own death/I don’t need no f-ing help” and a self-established fanbase, one cannot help but wonder how he would feel about his image molded by the hands of his estate (Genius).

Ultimately, the legacy of any celebrity is up to the fans that remember them. I had a discussion with my friends Christine Zhang (’19), Catherine Tanidjaja (’19), and Lexie Freeland (’19). Out of them, Christine Zhang (’19) only listened to X after hearing about his death, Catherine Tanidjaja did not listen to X’s posthumous release and Lexie Freeland (’19) has been listening to X since his debut album 17 and continued to listen to Skins after his death.

I asked them about their thoughts on Skins and Christine Zhang (’19) and Lexie Freeland (’19) both expressed that they did not like the album. Catherine Tanidjaja (’19) did not feel the need to listen to X’s work if it was not truly his own. Christine Zhang (’19) said, “I thought that they were worse. His old songs were full of emotion and there’s just no artistry behind Skins. When it came out and I listened to it, it didn’t feel like he was dead it felt like he made it and it was just bad.”

Lexie Freeland (’19) added, “Sometimes I don’t even feel like he’s dead people still talk about him so much that I feel like he’s still alive. He has become a part of our culture and that carries on with us even if he is really gone.”

Interestingly, the theory that X is still alive, and his death was somehow an elaborate publicity stunt still widely circulates amongst fans. The theory shows the denial and hope from X’s large and loyal fanbase that he built at the young age of 20. However, the proliferation of this theory rests on the accepted idea that the death of a rapper will make them more famous and that it would not surprise fans if a marketing team orchestrated the tragedy to for profit. This theory reveals that fans notice the underlying exploitative nature of all posthumous releases and almost expects it from large record labels.

When confronted with the moral conflict fans felt with the album, Lexie Freeland said, “He should have just left it at his old albums that were complete, but I also feel like he owed it to his fans to release what was left. I feel like if artists have unfinished music, especially if he died at such a young age, their fans deserve to hear it. And with so many teens that loved him so much. He contributed to the whole simp generation. He lowkey started the trend.”

“Sometimes I don’t even feel like he’s dead people still talk about him so much that I feel like he’s still alive. He has become a part of our culture and that carries on with us even if he is really gone.”

Hip-hop originated as a way for people to express their frustrations over the circumstances they would not change. Nihilism is understandably a common theme in rap songs. As its popularity in minority communities grew, the genre drew the interest of people from the outside. Major record labels saw hip-hop’s potential and capitalized on the opportunity to cash in. In the music industry, only a handful of companies decide the majority of what is played on the radio.

As a result, more and more artists started making content about money, drugs and violence because it appealed to larger audiences. Since hip-hop emerged as an original form of expression for predominantly black populations, the commodification of hip-hop cemented a ghettocentric image of what it means to be black. Underground hip-hop grew alongside mainstream hip-hop but fell into the same lyrical patterns in order to build and maintain an audience.

SoundCloud was a major platform for independent talent. As underground artists’ popularity grew, major labels quickly signed and amplified the platform’s biggest stars. They were deemed SoundCloud rappers or emo rappers because their lyrical content heavily referenced sadness, heartbreak and death. These themes appeal to teenage audiences that heavily consumed rap but grew up with punk rock. Two of the sub-genre’s most influential stars XXXtentacion and Lil Peep both achieved fame on their own before attracting record deals. However, influenced by the music that came before them, X frequently engaged in violence and Peep engaged in drug use. Almost as if fulfilling the prophecy they rapped about, they both passed away at an early age. Their fame attracted media attention which translated to more streams. Their respective record labels released posthumous albums on their behalf which artificially continued their musical legacies and thus, the monetary benefits as well.

For Peep, his album did not demonstrate the growth he was making as a human and instead, capitalized further on the drug use that killed him in the first place. For X, fans were disappointed in the album and was devoid of the complex emotions he poured into his earlier tracks. For an artist, their music is their legacy and especially for SoundCloud artists that rose to fame independently, they deserve control over how they are remembered. Whether it’s molding the hip-hop genre into a profitable and ingenuine model that generates profit and glorifies death violence and drug use, releasing an artists’ music after their death, major record labels have changed the authenticity of rappers’ experiences and music.

Anderson: https://www.amazon.com/Code-Street-Decency-Violence-Moral/dp/0393320782

Battan: https://www.gq.com/story/soundcloud-rap-boom-times

Battan: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/lil-peep-and-the-dilemma-of-the-posthumous-album

Beausoleil: https://medium.com/@beausoleil/the-rise-and-importance-of-emo-rap-d9b3d8ae004f

Berry: https://www.xxlmag.com/news/2018/10/xxxtentacion-17-wins-favorite-soul-rb-album-2018-american-music-awards/

Billboard Staff: https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/hip-hop/8461690/xxxtentacion-career-timeline

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/art/hip-hop

Caramanica: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/31/arts/music/lil-peep-archives-come-over-when-youre-sober.html

Caulfield: https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/chart-beat/8490709/xxxtentacion-skins-album-number-1-billboard-200-chart

Coe: https://www.xxlmag.com/news/2018/10/xxxtentacion-mother-charity-raffle-visit-mausoleum/

Collinge: http://dancemusicnw.com/posthumous-music-releases-editorial/

Genius: https://genius.com/Cold-hart-dying-lyrics

Genius: https://genius.com/Lil-peep-better-off-dying-lyrics

Genius: https://genius.com/Xxxtentacion-introduction-instructions-annotated

Genius: https://genius.com/Xxxtentacion-king-of-the-dead-lyrics

Giulione: https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/xxxtentacion-sad-number-1/

Ho: https://theoutline.com/post/6551/lil-peep-xxxtentacion-posthumous-releases?zd=1&zi=4adyqq76

IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm9425078/bio

Jeffries: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=a3bIlG3lrswC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=hip+hop

Cathy Yan (‘19) is a senior boarding student from Beijing, China. She calls Beijing home, but has also lived in Canada and the United States. Although...