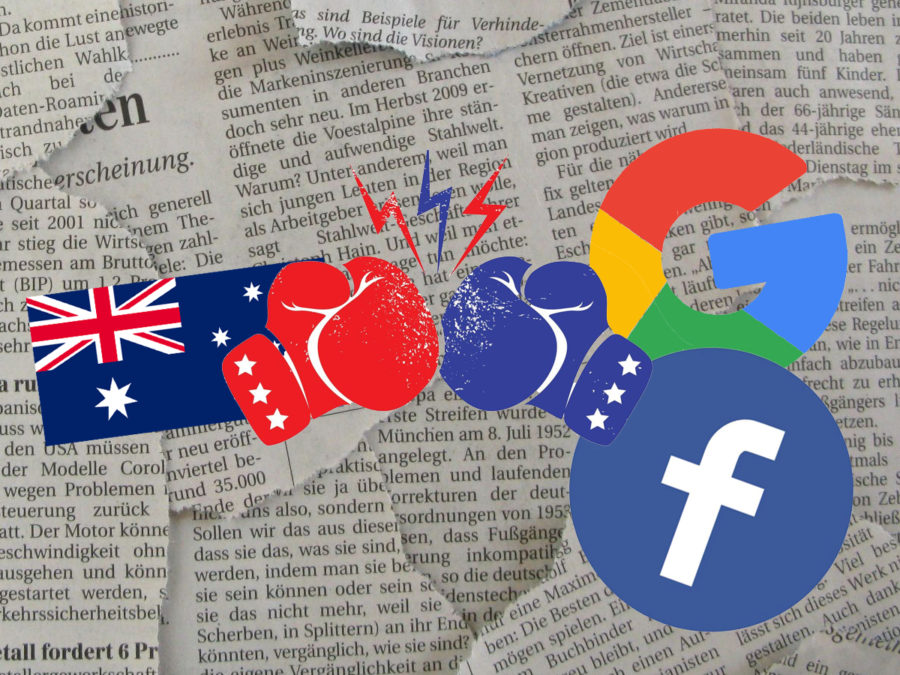

Since last December, the Australian government’s efforts to pass a new media law has evolved into a series of dramatic showdowns between the two power players: the government and tech titans, such as Google and Facebook. On February 25th, the law passed after modifications, requiring tech companies to pay publishers for features and links to their news content.

It appears that the government won this time, but this was only one small battle in a lengthy war.

Much of the world now acknowledges Google’s and Facebook’s dominance in the digital realm, with many deeming them monopolies. Governments in the past have attempted to break down these tech giants with antitrust laws, but their effort yielded little success. The Australian government’s decision to impose a new media law is a combination of an attempt to limit tech giants’ market power and a rallying cry to save the crippled traditional journalism industry.

Since the rise of modern–day media, traditional Australian media, News Corp and Nine, have lost millions of dollars in market value (News Corp at $14.8 billion and Nine at $4.1 billion), leaving them incomparable when placed next to Google’s $1.62 trillion and Facebook’s $964 billion market value. The reason behind the sharp decline is that these new tech giants have taken their advertising revenue. The new law, which obligates Google and Facebook to give part of their earnings to news publishers, aims to restore some balance to the market and support quality journalism.

“The news publishers were at the mercy of these social media groups because the social media were using their links and stories for free,” said Will Allan, humanities department faculty. “Once newspapers went downhill, a lot of news publishers and news organizations have had a tough time monetizing news, getting some sort of revenue online. So, it is a good way for the news agencies to stand up for themselves.”

Both Google and Facebook have publicly protested the law while simultaneously planning their exit strategies. Shortly after the announcement of the law, Google threatened to withdraw search from Australia.

Yet, that was all it was — a threat that never materialized.

As for Facebook, the platform briefly banned news pages amidst a pandemic and restored all functions a few days later. Both immediate responses were attempted bluffs. Google never intended to leave Australia, and Facebook never planned to ban all news for a prolonged period.

Google and Facebook also prepared long-term countermeasures. Google has negotiated with News Corp and more than 50 other Australian news organizations, while Facebook has struck a deal with Australian news company Seven West Media and is also on the move to sign with more publishers.

For many, the number of contracts and business deals in this situation is quite alarming.

“People get really sensitive when they hear the terms news and money together,” Mr. Allan said. “Because a lot of times when there is money involved, there’s corruption. When that involves the news, people are really sensitive because they want their news to be straight-forward and non-corruptible. People might worry that if there is a business deal involved, maybe the news isn’t as pure as they would hope.”

The government has gotten what it wanted, with minor compromises. However, the effectiveness of the law remains questionable. While the law comes from good intentions, it will likely do very little in restricting the power of Google and Facebook because the payment is only a tiny, insignificant fraction of their revenue.

Of course, with the government being the mastermind behind the push, there are concerns over the role of government in regulating a market.

“Some people are just adverse to the government being involved with private entities, so that could raise some alarms too,” Mr. Allan said.

Ultimately, the law does not help those who are the most vulnerable or those who truly need help — the public and small news publications. The law does not restrict the media influence of these platforms, which we have seen in recent circulation of misinformation and extreme hate speech.

In addition, the law hurts small news agencies, who are already struggling to survive, and only benefits traditional media barons like Rupert Murdoch. Small publishers are ineligible to participate in the compulsory arbitration program, which is key for the law to be effective, because the program requires the business to make a certain amount of revenue and create predominantly Australian content.

While Australia’s new law will likely have a limited impact on both the tech monopolies and the struggling news publishers, it shows a promising future for similar policies. With this media law as a global precedent, many other countries, including the United States, Canada, and those in the European Union, have expressed interest in adopting similar measures.

![All members of the Webb Robotics Winter season teams taking a group photo. Of note is Team 359, pictured in the middle row. “It was super exciting to get the win and have the chance to go to regionals [robotics competition]” Max Lan (‘25) said. From left to right: Max Lan (‘25), Jerry Hu (‘26), David Lui (‘25), Jake Hui (’25), Boyang Li (‘25), bottom Jonathan Li (’25), Tyler Liu (‘25)](https://webbcanyonchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-10-at-2.41.38 PM.png)