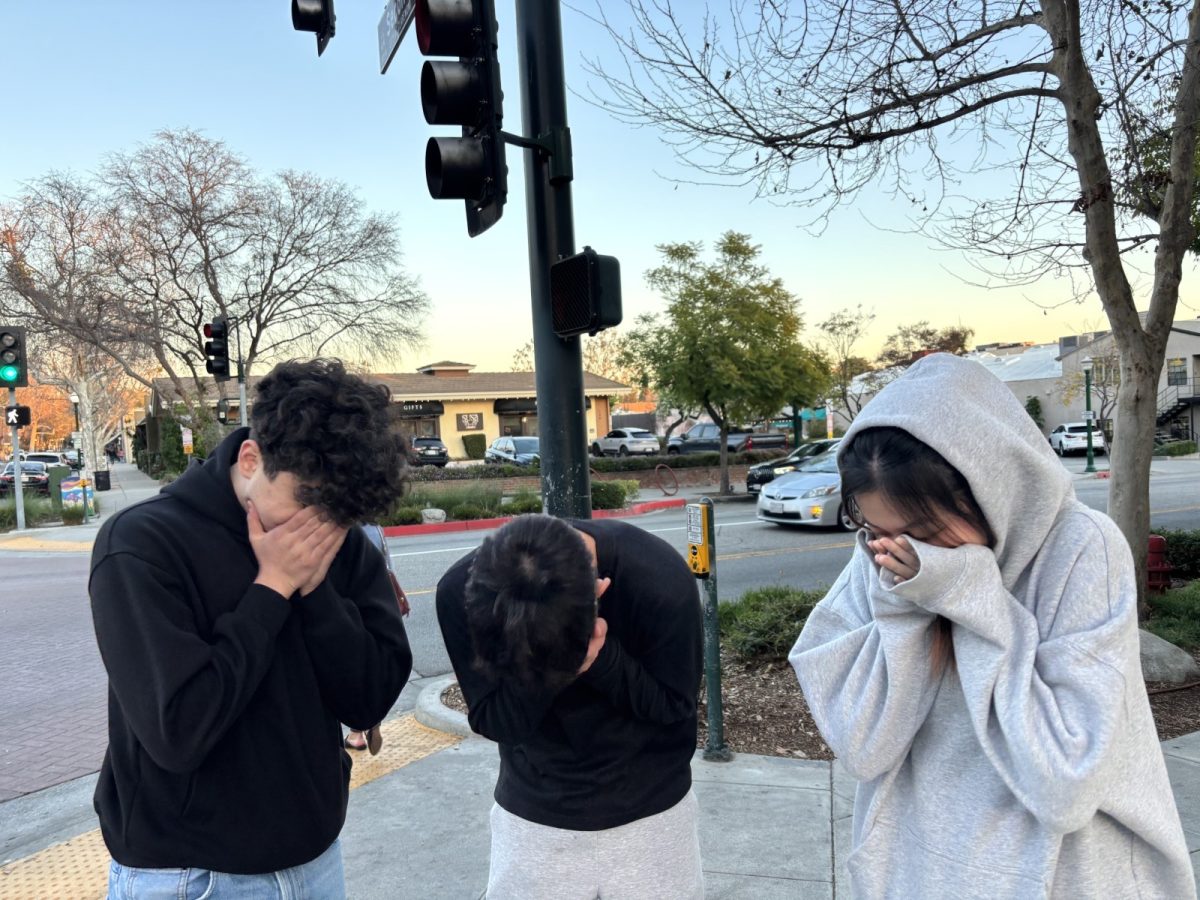

“Dude, I slept for like two hours last night.”

“Yeah, well I have two in-class essays this week and a math test. I wanna die.”

“Same though, but lemme apply to college first.”

According to a survey sent out October 16, 2017, 68 of the 73 Webb students who replied have participated in a conversation similar to the above at one point in their Webb career. In a high-intensity academic environment, it is easy to fall prey to gaining validation through comparison, personal sacrifice equivalent to how much you “care” about grades, or your future, or whatever you are most insecure about at the moment.

Mixed within these conversations are casually used yet alarmingly morbid phrases like, “Kill me now,” “Everything sucks,” and “I’m literally dead.” A culture of self-deprecation is apparent at Webb, but it may be connected to a larger generational phenomenon of bombardment, an inundation of news, events, and expectations that does not allow for sufficient time to react before the next big thing hits us.

Humanity displays an innate desire to connect and communicate, cultural norms acting as the thread that ties us to one another. Melanie Bauman, Director of Counseling and Health Education, believes that the language of an environment, especially a high-stress one, allows Webb students to feel as if they are connecting through the pain. If a student chooses not to participate in this type of dialogue, like the 7% surveyed, they are immediately “othered,” an inherent fear each one of us tries to suppress.

Social media has created a culture of shared experiences, but also “unfiltered” and “pieced” reality, in the words of Bauman. When we see someone else’s Snap story and compare it to our reality of homework on a Saturday night, we internalize self-imposed and cultural pressures, leading us to engage in unhealthy dialogue as a coping mechanism.

Bauman referenced the app TBH, a simple game that offers a positive prompt like “Best Hair,” followed by four people from your school. Each gem offers a small amount of dopamine, tapping into our natural longing for validation, and the app’s short-lived yet intense popularity on the Webb campus exposed our love of immediate affirmation, coupled with anonymous esteem-building phrases.

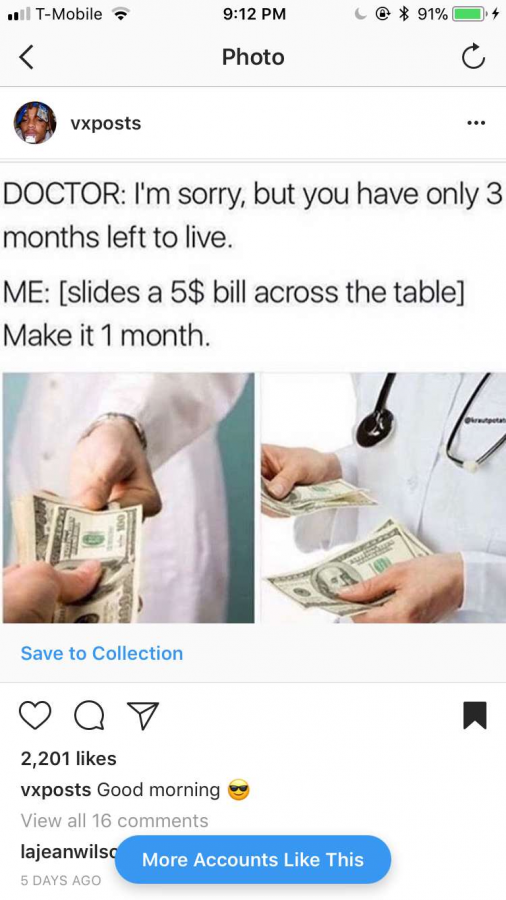

While apps like TBH experience short-lived success, a scroll through the Explore page on Instagram or a Twitter feed proves that our generation of humor and relatability is rooted in sarcasm, cynicism, irony, and absurdism.

These sentiments are aggravated in high-stress environments. Since we are constantly overwhelmed by tragic news, homework assignments, and friend drama, we do not have enough time to simply think. Sometimes, it feels like each idle second is a second wasted, when, in reality, it is in those moments we can find solace and reflection essential to a healthy lifestyle because no one actually wants to stay up until 3 a.m. working.

According to Veronica Faison of The Odyssey, it is easier to post a caption with an out-of-context photo than it is to confront tragedy or inconvenience. Technology allows us to access a mountain of information, sometimes without our approval. While this has its benefits, we have become jaded to truly horrible news, indifferent to all that pulls us in every other direction.

While virtual satisfaction and complaining may feel cathartic, Bauman emphasizes that connecting around pain is not healthy. Loathing the homework we have to complete does not get us any closer to completing it. The first step to improving our state of mind is to acknowledge that a problem exists. While 54% said their comments are “not that deep,” we can at least recognize the culture we are creating and decide for ourselves if we want to participate in it.