Empathy is one of the defining features of our Webb experience. From freshmen seminar to self-reflections, from advisory check-ins to humanities discussions, students learn to stay true to their opinions while respecting and listening to the voices of their peers.

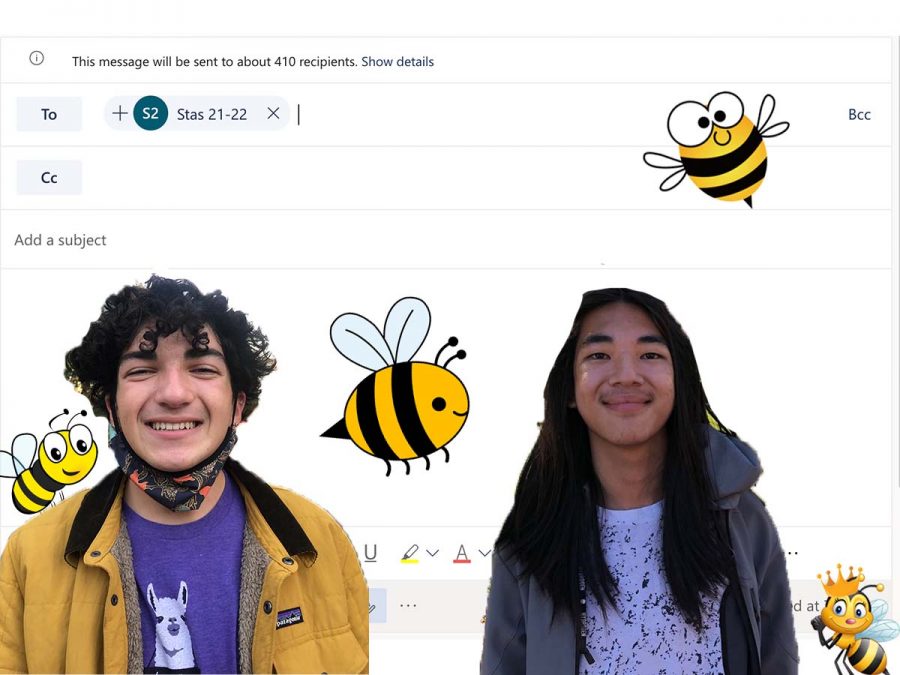

When students received the news of disoriented bees storming the library, different perspectives on the issue sparked discussions on STAS. However, conversations on the email chain soon took an unexpected turn. From students expressing concerns to others sharing relevant information, more and more students joined the conversation, but many contributions became personal attacks directed at specific responses and even the individuals behind the emails.

Whether it be environmentalism, social justice, or free speech, we all have issues that we deeply care about. Despite knowing the importance of respectful conversations, it is easy for students to assume a moral high ground, thus undermining, often unconsciously, the validity of others’ opinions and even them as individuals.

“I wanted to show that [my first email] was not an attack on anyone, but rather a start of a conversation,” Hunter Lange (‘22) said. “But one thing I was upset about was that people started going after whoever they disagreed with, and I did not think it was fair. The whole point is to raise awareness and begin the conversation, instead of starting a fight.”

Zac Wang (‘23) replied to the email chain and provided information on the difference between invasive bees and indigenous species. Although he did not intend to undermine the opinions of others, the responses backfired and turned into aggressive comments.

“I had someone come up to me and say, ‘Zac, you started the opposition. You gave us a chance,’” Zac said. “But in reality, I did not do anything. I put facts out there. I wasn’t upset by the fact that people use my email to rebound off [of], I was more upset when after that, people were directly attacking others and their opinions.”

Ironically, students who disagreed and filled STAS with one scathing email after another agreed on one important issue: no one desired the extermination of bees.

To “pro-bee” students, the other side was apathetic, unkind, and unempathetic of animals and the natural world. To the “anti-bee” students, the other side was irrational, insensitive of student health, and showed minimal understanding of the school and those who handled the situation.

It is important to note that Hunter’s original post was neither “pro-bee” nor “anti-bee.” It was a call to rethink how our community responds to situations involving risk.

At the end of the day, neither “pro-bee” nor “anti-bee” students wanted to compromise student health or kill bees, but disagreements persisted and both sides continued to be intolerant of the other side.

Many students who shared their personal opinions on STAS confronted passionate, dissenting arguments from other students. Both “pro-bee” and “anti-bee” students found the other side to be unbelievably stubborn and unreasonable. These disagreements led to extreme polarization that resembles our current political climate: people divided into the Left and Right with no empathy for the other side.

Online communication has made it even harder to comprehend and empathize with others without the outrage and frustration that accompany it.

“It is important to hear people’s opinions, but it’s also important to know all the information before you decide to make official statements, and that’s why it was hard to have it on email,” said Nathan Hubbard, library staff. “It was similar to social media posts.”

Even in a school that actively teaches students to engage in civic discourse, the email exchanges showed how easy it is for things to go downhill. One morning, the STAS emails became what one student jokingly called “angry Twitter fights” and became a miniature of social media fights that we often see online.

“I feel like the best way for me, at least, is to have a physical conversation,” Zac said. “There can be a lot of miscommunications online, as well as a lack of sympathy and empathy, and this was why I wanted to hold the bee conference.”

Social psychologists summarize five reasons why we are fighting on social media, which include interpretation errors, cognitive dissonance, attribution error, confirmation bias, and social reinforcement. In simpler terms, our brains are structured so that we are stubborn; we are uncomfortable when our beliefs are challenged, we hear what we want to hear, and finally, we opt for groups that we identify with and find comfort in. This is human nature.

It is not our fault, but we should combat the neurons in our brains that are alienating, dividing, and polarizing us.

As we have seen from the email chains, once stirred by such psychological impulses, even good intentions can turn into aggressive attacks. Students chose sides, and diversity of thought was immediately reduced into polarization.

It is not to say that we should denounce disagreements altogether. On the contrary, for our community to thrive, we need conversations, and we need disagreements, but the STAS discussions taught us that we need to communicate in a way that makes them meaningful. So how do we do that?

First, we need to inform ourselves. Before sharing any opinions, use available information and sources to inform your opinions before jumping into the conversation and choosing a specific side.

We do not always need to choose sides. By doing so, we simplify an originally complex problem into a “yes” and “no” solution that fails to encapsulate the essence of disagreements. In order to ensure the diversity of thought in each discussion, we should stay away from picking sides and instead acknowledge the complicated nature of each discussion, making it possible to find common ground.

Instead of making assumptions about the other side, we should practice empathy and appreciate differences. By examining our own biases and how our brains work, we can become calmer and more informed in the face of heated debates.

Although the STAS emails elicited an unpleasant experience for some students, it demonstrates the need for our community to engage in truly civic discourse with composure, especially during a global climate of political polarization.

“We are a colony, just like the bees, and there is a lot that we need to learn,” Hunter said.

We should continue tackling important topics and do it with grace and grit.

![Many Webb students spend their free time in the library watching a popular TV show like Riverdale and Euphoria. “Based off what I’ve seen, like in Euphoria, because the actors are older, they don't showcase an actual high school life properly,” Sochika Ndibe (‘26) said. “Since [the actors] are older [and] playing a teenager, from a girl’s perspective, it is going to make you think you should look more developed at a young age.” The actor, who plays Veronica Lodge, was 22 years old at the time of filming.](https://webbcanyonchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Antecol-Media-affects-how-society-functions-graphic-1200x900.png)