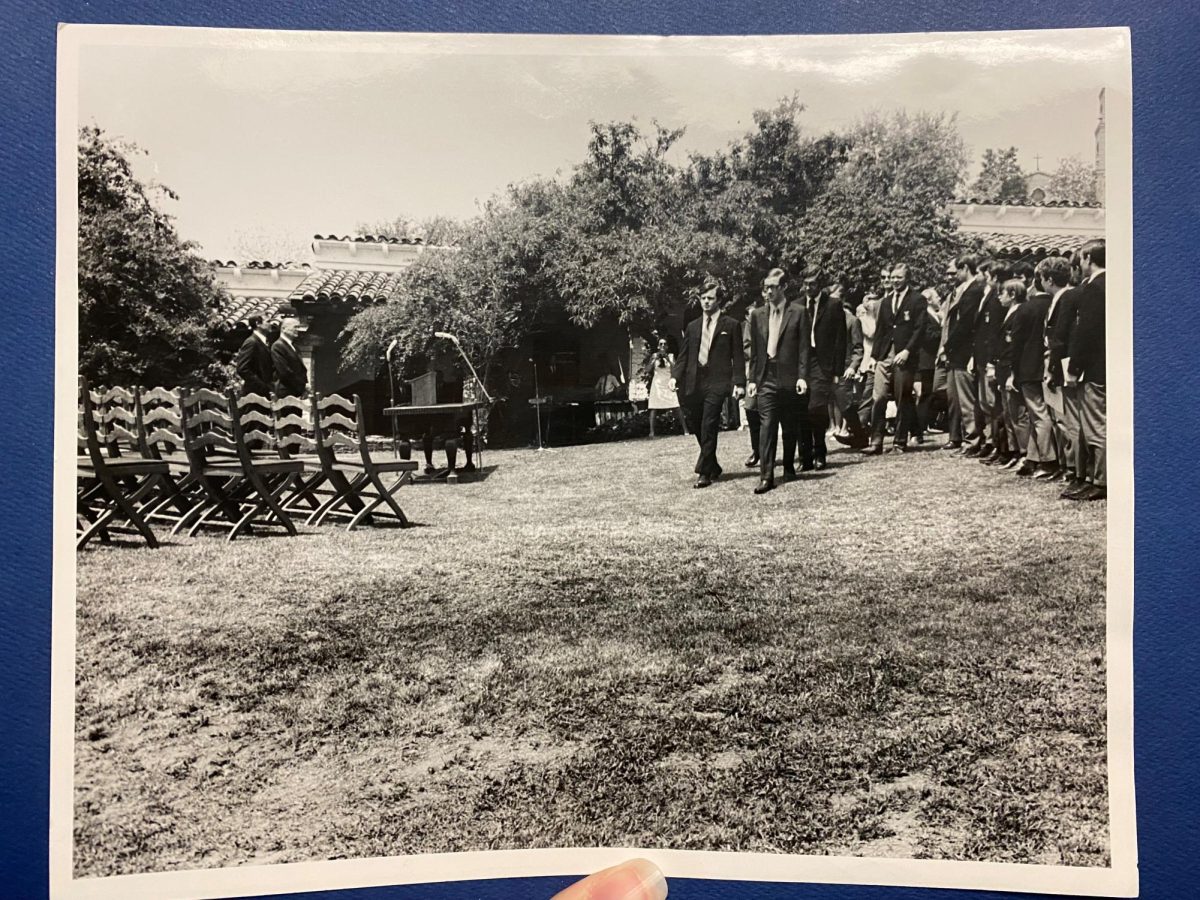

Traversing across oceans, American Society: Past and Present illuminated a new narrative of the past, one that multiplied simple dates and numbers that I had learned before the American Society curriculum. Learning American history became unprecedentedly refreshing at Webb. Foner’s passages on Frederick Douglass, the ghost dance, and the Bracero Program supplemented bland facts that I memorized from Chinese textbooks.

On October 8th, Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 101, a legislative mandate requiring ethnic studies as part of the graduation requirement for high school students beginning from the class of 2029, making California the first state to include ethnic studies in every high school.

Under the Model Ethnic Studies Curriculum, each public high school in California must incorporate ethnic studies into their history and English curriculums no later than the 2025-2026 school year, and the graduation requirement will take into effect beginning from the 2029-2030 school year.

It was not easy for Newsom to pass the bill amidst the national debate on the proper roles of history education. While proponents of critical race theory argued for the importance of educating students about the lasting effects of historical inequality and institutional racism, critics argued that such an approach would only reinforce racial divisions, which is why many states have already begun banning critical race theory in history education.

To future students in California, the bill means that they will learn about the ways that African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and other racial and ethnic groups contributed to the nation’s past. Exposing students to experiences of different groups, the new curriculum model seeks to incorporate the histories of diverse populations in California into history education.

To many high schools in California, the bill means that they will make major adjustments to their Humanities courses to accommodate content in the new model, which is why the enactment of the bill releases $50 million out of state budget for schools to develop the curriculum.

To Webb, the bill is a reaffirmation of the humanities curriculum’s commitment to exposing students to multi-narratives—something that students learn as early as in freshmen year’s core classes. As stated in Webb’s Course Selection Guide, humanities education aims to help “students cultivate a culture of thinking that crosses the lines of traditional kinds of texts.”

As a private school, Webb is not directly affected by the law, although the future ethnic studies requirements of the UC system will eventually mean that Webb also has to make adaptations. Fortunately, Webb already meets all the requirements. Moreover, many electives that students take during their junior and senior year already incorporate ethnic studies.

“I think it is wonderful that the state of California is prioritizing the important changes that need to be made in traditional American history curriculum,” said Jess Fisher, chair of humanities and history. “For so long, American history has been taught in the lens of white America only, and the narratives that the law identify have incredibly important parts in US history. When we see the specific requirements, we will make sure to be not only satisfying but also exceeding them as we want all students to see themselves in the curriculum and develop empathy.”

At Webb, students learn to become critical thinkers through critiquing the danger of “a single story.” This approach especially shines through in American Society: Past and Present, Webb’s unique American history class that already entails elements of ethnic studies. The Course Selection Guide describes the class as equipping students to “consider the many narratives, identities, values, and cultural phenomena that are the driving forces and products of American experiences.” Through examining different “narratives, identities, values,” students can develop a more critical and insightful understanding of contemporary social challenges through a historical lens.

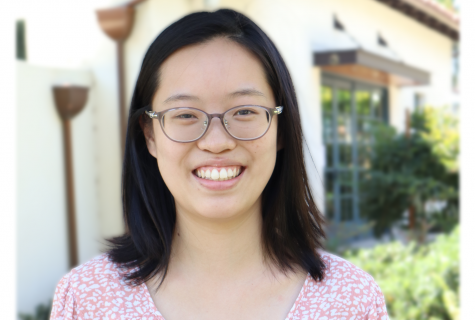

“In middle school, history was all about memorizing facts, and the tests were based on numbers and dates,” said Annie Han (‘24), an American Society student. “At Webb, we are reading primary sources and seeing different perspectives. We look at the perspective of slaves as well as slave owners, and we also analyze the texts.”

The way that Webb teaches history clearly eliminates critical race theory critics’ concern that teaching the history of racism only advances the liberal political agenda and brainwashes students into blindly supporting identity politics.

One advanced studies course Literature of Revolution & the Atlantic World, for example, entails a unit that encourages students to conduct in-depth research into the Revolution experiences of Native Americans, African Americans, and women beyond the white, middle-class narrative.

“It doesn’t seem to me that there’s anything involved politically at all, other than trying to tell the nation’s history as completest as possible,” said Susanna Linsley, director of experiential learning, “And that is the role of history. It is not a choice to leave people out.”

In fact, understanding the connection between the Trail of Tears, modern-day reservations, the Civil Rights Movement, and Black Lives Matter drew me closer to classmates who all desire justice.

In Society, we shared thoughtful ideas, never reducing our levels of thought to the simple dichotomy of the oppressors and the oppressed that critical race theory critics espouse. Outside, we sought to create collaborative spaces as allies and friends.

What was dubbed “state-sanctioned racism” by Gov. Ron DeSantis enlarged my vision. What he claimed to “teach kids to hate each other” taught me how to better understand, appreciate, and love the education that I have received.

“Teaching the history of Americans of all races is not teaching racism. If anything, it is helping to unteach racism,” Ms. Fisher said.

The ethnic studies graduation requirement can combat ignorance, while the boycott of the 1619 Project and the banning of critical race theory in education signals danger. I fear that, like the Chinese textbooks on United States history, future classes will only have students ask, “will the date of the Gettysburg address be on tomorrow’s quiz?” and not: where do these narratives converge? How do we avoid the same mistakes?

Critics think that teaching the roots of racial and social inequality further breeds division and hate, but what it actually does is deepen our understanding of current problems, expanding our visions across texts and sources, and ultimately giving us the power to formulate a version of the past that satisfies our curiosities for the truth, often with depth and disturbing complexities.

“From Society, I’ve learned that it’s important to look at different perspectives,” Annie said. “I’ve learned to consider different sources to formulate my own thinking.”

The Webb humanities program alone proves that incorporating ethnic studies and critical race theory in history education is not a sign of political depravation, but rather a necessity for students to become better thinkers capable of drawing connections across the many documents and media they consume.

This is why we are learning about Toypurina and the San Gabriel Rebellion to inform our understanding of the current border crisis in Advanced Studies Culture & Politics of the Border. This is why in Advanced Studies Literature of Revolution & the Atlantic World, we spend a unit researching the changes and continuities that the war brought to not only patriots, but African Americans, Native Americans, and women so we can truly “consider the conflict through multiple lenses, perspectives, and identities.”

“I want students to have a 360-view of the American Revolution, to understand all groups that were involved, to really let students spend time with different stories and see the American Revolution as a layered collage of human experiences and stories,” Dr. Linsley said.

By taking on an analytical and comparative lens to study history, our reading and writing becomes more meaningful. We can learn how history has shaped inequality without blindly placing the blame, and we can truly become better historians.

After all, “liberty” is an empty word if we do not understand the complex history behind such ideals. A ban on critical race theory offers no solution, while an expansion of ethnic studies across California can help us redefine what liberty means to our predecessors, and finally, to us.

![Many Webb students spend their free time in the library watching a popular TV show like Riverdale and Euphoria. “Based off what I’ve seen, like in Euphoria, because the actors are older, they don't showcase an actual high school life properly,” Sochika Ndibe (‘26) said. “Since [the actors] are older [and] playing a teenager, from a girl’s perspective, it is going to make you think you should look more developed at a young age.” The actor, who plays Veronica Lodge, was 22 years old at the time of filming.](https://webbcanyonchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Antecol-Media-affects-how-society-functions-graphic-1200x900.png)