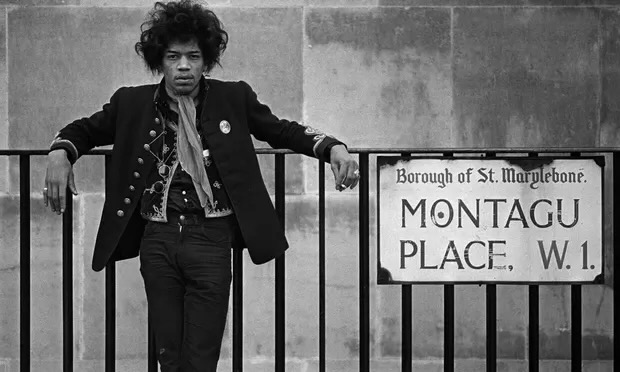

“I expected more from you” is a phrase frequently encountered in the comment sections of celebrities on Instagram. Under the guise that social media is real and comments matter, fans use this public space to express their disappointment with their favorite public figures’ perceived lack of social justice actions. The expectation is that anyone with influence should use their platform to speak on issues like war, tragedies, and injustices. The statements they make must be universally agreeable to ensure the continuity of their careers. However, this demand for political correctness compromises both their art and personal ethics, as any potential deviation from expectation renders their efforts “offensive” and “distasteful” in the eyes of fans. Audience demands for political activism from artists, specifically those of color, operate hand-in-hand with idealizations of public figures and are a hindrance to the potential of the actual art being created. Jimi Hendrix’s public reception operates as an example of this, as despite his lack of direct political action in the media, fantasies of his social justice work prevail in his legacy.

Jimi Hendrix’s existence as a successful Black musician functions as a protest against societal understandings of rock and roll music, as well as a system that actively worked against people who looked like him. However, as we perpetuate a fictitious image that turns Hendrix into a figure he was not, we obscure his real legacy and undervalue his art.

Born in Seattle, Washington as Johnny Allen Hendrix, his early life mirrored that of many Black Americans in the forties. Born into poverty, his father’s absence during his birth due to an inability to be granted standard military furlough marked the beginning of a life full of injustice. Hendrix’s own life reflected his father’s in many ways, as he, too, never graduated from high school. However, throughout any hardship he faced, he found solace in music.

At 18 years old, Hendrix was caught riding in a stolen car for the second time. Given the decision between a potential 10-year prison sentence or joining the army, Hendrix again followed his father’s path and chose the latter. He was discharged after a year due to his physical unsuitability and his inability to assimilate with the other soldiers. Even while stationed in Kentucky, he begged his father to send him his guitar. His father obliged, and Hendrix formed a band on the base. One letter explaining his discharge states that he “cannot function while performing duties and thinking about his guitar.” Jimi Hendrix Army Discharge paper – The Gibson Lounge

After his discharge in 1962, Hendrix immediately formed a band with a fellow discharged soldier. The following three years featured a focused Hendrix and his path to musical stardom. He was noticed by Chas Chandler, a bassist, record producer, and manager in Greenwich, New York. He immediately adopted Hendrix as his own and encouraged his relocation to London, believing that its burgeoning music scene was the perfect environment for Hendrix’s sensibilities. After moving to London, Hendrix changed his name from James Marshall Hendrix to Jimi, signifying a deliberate distance from his past.

This transformation marked the birth of a new artistic persona. In many promotional posters for concerts and festivals Hendrix performed at, he is written as being “from London, England.” Despite being linked to Laurel Canyon, he spent the majority of his years in London until his death in 1970. This intentional obscuring of his geographic origins challenged traditional ideas of nationalism and broke the fantasy many fans continue to project on him. This misconception about his origins contributes to the fantasy projected onto him as an all-american musician.

The fan idealization of Jimi Hendrix has contributed more to his legacy than his actual art. As a prominent black rock and roll artist in the sixties, he faced unrealistic expectations from white audiences who envisioned him as a Black Panther-like figure. The demands for racial justice from the Black Panther Party led to a connection between any black artist and these beliefs. Additionally, many white fans saw him as a hypersexual racial stereotype instead of a serious musician. His white audiences noticed Hendrix’s race, as it was a selling point when he initially burst onto the rock and roll scene. However, they exploited his race to fit into their specific fantasies about him and his sexuality. The media during this time extended this stereotype with Rolling Stone magazine calling him a “Psychedelic Superspade” and another magazine calling him the “Wild Man of Borneo.” How Jimi Hendrix’s race became his ‘invisible legacy’ | CNN This confirmation of Hendrix’s idealized figure by news sources widely regarded as reliable has not only obscured his legacy but also impacted the way in which black audiences viewed him.

Two weeks after performing at Woodstock, Hendrix offered a free concert for a group he called “my people.” He held a concert for a black audience in Harlem, a place he lived before leaving for London. As he stepped on stage, someone threw a bottle at him that shattered against a speaker, and eggs splattered on the stage. He continued to play as the crowd slowly left. He played this concert in an effort to connect with Black people who believed him to be a musical Uncle Tom. His apolitical stances and belief in nonviolence and peace isolated him further from black audiences. The expectation for political beliefs solely based on ethnicity became an oppressive act, with Hendrix caught between the disdain of black audiences and the embrace of white audiences.

The way Hendrix’s powerful rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” at Woodstock in 1969 became the iconic image of anti-war protests of the period is a prime example of this fantasy being projected onto him. While this performance does have overt political tones, compared to actual protests against US actions in Vietnam and steps taken by various young political organizations to educate the masses on the subject, this seems like a molehill. During a Dick Cavett appearance in 1969, Hendrix was asked about his take on the anthem and said, “All I did was play it. I’m American, so I played it.. it’s not unorthodox. I thought it was beautiful.” The number of think pieces written about this one performance exhaust the work of art and turn it into something it wasn’t. The audience that witnessed it, which was predominantly white, described it as one of the most important acts of protests of the sixties. Even today, professors such as Dr. Jeremy Wells How Jimi Hendrix’s race became his ‘invisible legacy’ | CNN holds his performance in the highest regard, claiming it to be on par with Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

The public treatment of Jimi Hendrix demonstrates how fantasies obscure fans’ true desires for artists. Any direct action that Hendrix could have taken against this image painted of him would have disrupted the fantasy and awoken the viewer from the dream. White fans perceive Hendrix as one of the most powerful political figures of the sixties, while black fans see him as a sellout. Through this idealization, it becomes almost impossible to understand Hendrix’s true artistic legacy. The idea of him became much more important than who he actually was. Through examining the facts of his life, one would discover a musician who loved music and followed his passion until the end of his life. His early life resembled that of many black Americans in the forties and fifties, but it does not necessitate the same response.

In the end, Jimi Hendrix was not an activist; he was an artist. It is time to allow artists to be just that. In demands for political activeness from artists, we distract from the importance of the art itself. Lack of media comprehension and conflating personal identity with political stances reflect a broader issue of lack of funding for the arts in our society. To truly value art, the reign of artist celebrities must end. Hendrix rarely participated in activist work, yet that is one of the only things remembered about him as opposed to his musical masterpieces. When we begin to care more about the artist than the art, we will truly be able to value the art itself.

When speaking to a New York Times reporter in 1969 Black History Month Spotlight – Jimi Hendrix – K-ROCK 105.7, Jimi Hendrix said, “Sometimes when I come up here, people say, ‘He plays white rock for white people. What’s he doing up here?’ Well, I want to show them that music is universal – that there is no white rock or black rock.”