Final set. Four games all. 30:30.

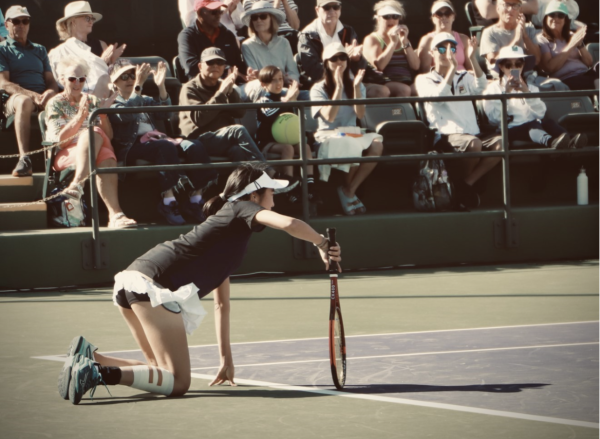

The brutal early afternoon sun scorches the top of her scalp. A drop of sweat slips into her eye. A sharp sting, a blink, then a brief blur. Her injured leg, wrapped in compression tape like a burrito, moves like lead. The opponent’s serve lands cleanly—she scrambles, manages a return, and rallies. But then, the opponent strikes a screaming backhand down the line. Her calf seizes. She stumbles, reaching – too late. The ball streaks past.

40:30.

Aoi Ito must win the next point.

Ranked world No. 106 at the time, Ito had to battle through two rounds of qualifying to secure a spot in the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) 1000 Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP) Paribas Open main draw in Indian Wells, California.

Out of 48 qualifiers, only 12 advanced. For a rising Japanese player like Ito, each victory was not just a step onto the big stage —it was also a means to cover her travel and hotel expenses.

Down 30:40 at four games all in the third set, the match teeters on the edge. Losing the point puts a lot of pressure on your next service game, which you must hold to stay in the match. Win, and momentum swings your way—one step closer to deuce, to a break, to seizing control of the match.

A few points ago, she had over-rotated on a forehand, her foot slipping on the sunbaked court. Pain shot through her calf, and she fell to the floor. The trainer was called immediately, rushing onto the court with an ice pack and compression tape.

Murmurs spread through the crowd. Spectators leaned in, whispering. A tournament staff member pressed his walkie-talkie to his mouth.

“She’s hurt bad,” he said. “Potential walkover on Court 7.”

Yet, after fifteen minutes, Ito rose. Still limping, she walked to the deuce side as the crowd cheered her on. Even though the compression tape on the calf eased the pain, the injury had taken her greatest weapon—her agility.

“Some of my favorite Asian tennis players like Kei Nishikori and Jerry Shang are great movers,” said Jonas Sun (‘25), a varsity player on the boys’ tennis team. “They use their speed and movement to create extreme angles, forcing their opponents out of position.”

The same can be said for Ito. With her small frame, she developed a distinctive playing style from a young age.

“I think my forehand slices have improved the most,” Ito said during an interview with WTA. “I can use them for both defense and attack.”

Rather than relying on a conventional topspin forehand, she often disrupts rhythm by switching to a slice forehand down the line during crosscourt rallies – a shot that neutralizes the raw power many European and American players generate on their forehands.

“I can see their playing style blending into mine,” Jonas said. “I like playing defense and waiting for my opponent to make the mistake rather than just slapping a winner to win every point.”

At 30:40, Ito faces the powerful strokes of her Ukrainian opponent, Daria Snigur. Taller and significantly heavier, Snigur uses her physical advantage to dictate points with her heavy, penetrating shots.

But Ito counters with precision. Placing her shots deep into the court, each kissing the sidelines, she forces Snigur into awkward positions. The pressure mounts, and two unforced errors follow.

Now, Ito has a break point. This is her chance.

Snigur strikes a kick serve to Ito’s backhand. She leaps, taking the ball early and pushing it to a short angle to Snigur’s backhand, pulling her to the double’s alley. Snigur responds with a heavy backhand, but it slows down her movement.

Tennis is a game of strategic trade-offs—a slice may make footwork lighter but leaves the shot vulnerable, while a proper groundstroke requires stable foot positioning for better shot quality. Seeing Snigur’s foot planted on the ground, Ito strikes a backhand down the line. Snigur gets to it, but her footwork is disrupted.

Ito quickly adjusts, mixing her topspin forehand with slices that land short into the court, forcing Snigur to move forward. This constant pressure wears her out, and with a backhand that had just a little more sidespin than usual, Snigur miscalculates the ball’s distance. The frame of her racket connects with the ball, sending it wide.

5:4. Ito had broken her.

Now in the lead, Ito mixes a variety of shots to close out the match. Her signature slice and topspin backhand keep Snigur’s aggression at bay, and she even moves forward to execute a drop volley at 30–30, using the moment to seize control.

Ito’s victory at Indian Wells highlights the resilience and ingenuity many Asian players bring to the professional tennis circuit. With their unique styles and tactical intelligence, they challenge the dominance of physically imposing players, proving that speed, precision, and adaptability can be just as effective as raw power. However, Asian tennis players often face unique challenges in their journey.

“In many Asian countries, you rarely see tennis courts being open to the public,” Jonas said. “To play, you must reserve a court and pay a lot of money.”

Tennis is not as widely cultivated as a sport in many Asian countries, and access to courts is limited – often requiring players to pay for court time, which restricts their development compared to athletes in regions like the U.S. and Europe, where tennis is more ingrained in the culture.

These challenges highlight the need for greater recognition of Asian tennis players, as visibility is crucial for attracting sponsors and resources that can provide the necessary support for their growth and success.

Still, players like Ito continue to rise through the ranks, showing the world that determination and strategic brilliance can transcend physical limitations.