Consciousness is thought to be a trait shared between only a few species, but scientists and programmers are coming close to creating machines that are self aware. Having already created robots such as IBM’s Watson, MIT’s ELIZA, and Hanson Robotics’ Sophia programmed with artificial intelligence, it has been demonstrated that having a conversation with a robot is possible, and these clever machines are even eligible for citizenship. Where one draws the line between human and machine is becoming thinner and thinner.

Isaac Asimov’s three basic laws of robotics are: a robot may not let a human come to harm, a robot must obey orders given to it unless said orders violate the first law, and a robot must protect its own existence as long as the circumstances for protection do not violate the first or second laws. Because artificial intelligence has the potential to become so complex, it might be able to just choose not to follow orders entirely as a freethinking entity.

Last year, James Demetriades, Webb alumnus and founder of Kairos Ventures, came to give a Sunday Chapel speech at Webb about advancements in technology. When questioned about his opinion on what laws there are or should be around artificial intelligence, Demetriades answered, “I don’t know, that’ll be up to you guys to decide.” This unpreparedness worried students and faculty alike, raising questions on how well people will be able to handle technology in the future.

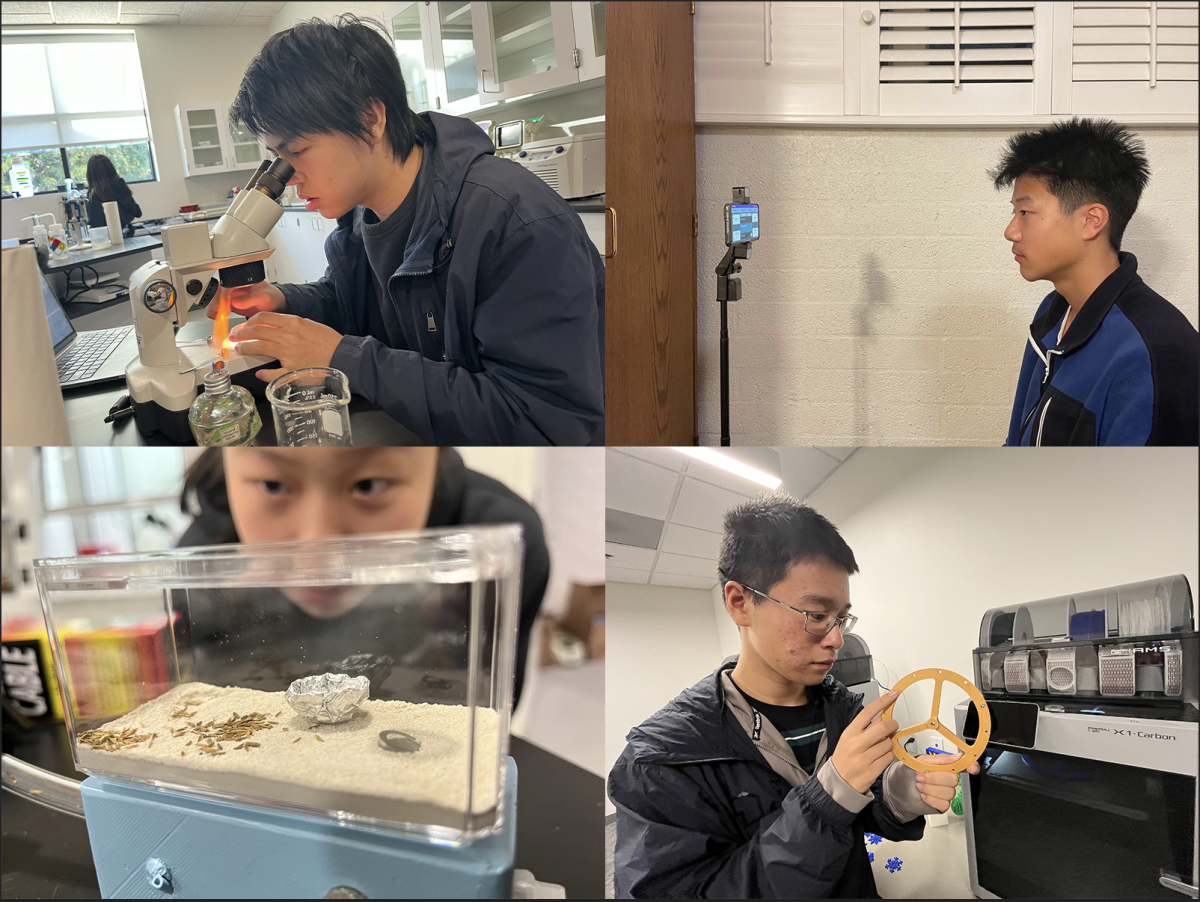

Tony Xiong (‘19) of the Webb Robotics team said, “The people who create things don’t necessarily think of the outcome of what they’re making.” He made a comparison to nuclear devices, and how the results were not thoroughly studied before using them. Lawrence Mao, another member of Webb Robotics, made a comparison to GMOs, saying, “with GMOs, we change the genetic code of a plant and test to see if there are any consequences that come with it. Only after several tests are performed can we trust it, and the same thing applies to A.I.”

The book Constitution 3.0: Freedom and Technological Change by Jeffrey Rosen and Benjamin Wittes (which can be found at your local Webb Fawcett Library) touches on the laws corresponding to artificial intelligence in the chapter “Endowed by Their Creator? The Future of Constitutional Personhood.” James Boyle presents a fictional example of a program called Hal which wins the Loebner prize (a prize awarded to the most human-like AI) since its typed responses cannot be distinguished from that of a human’s. Hal then turns on his creator who won the cash prize and medal instead of Hal, and is even able to contact the FBI and claim its creator was violating the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments.

While this is a fictional situation, it brings up an important question: if a machine capable of human-like thoughts, emotions, and consciousness is created, is it entitled to the same rights as a human? MIT professor Rodney Brooks says, “we are all machines. We are really sophisticated machines made up of billions of billions of biomolecules that interact according to…rules deriving from physics and chemistry.”

If this is so, then surely any other machine working under the same or similar circumstances would be a human too? Professor Brooks speaks again:

“If…we learn the rules governing our brains, then in principle there’s no reason why we shouldn’t be able to replicate those rules in, say, silicon and steel. I believe our creation would exhibit genuine human-level intelligence, emotions, and even consciousness.”

So if Hal’s “mind” acts so similar to that of a human’s, is he right to have rights? The idea of “personhood,” or determining whether or not a being falls into the legal category of “man,” is important when determining the validity of an argument. Recently, it was claimed that a horse could sue for damages in court, so why can’t a competent computer?

According to the Declaration of Independence, they just might be able to. Because an A.I. capable computer is a thinking entity, it would be able to make the argument that it is “endowed by [its] creator with certain unalienable rights,” and cite their creator as the one who made them. One could refute this and say the computer is not a man, but why? What can a person do that a machine could never perform? Perhaps the most important question is not “what” or “why,” but rather “why not.”

To give a machine the same legal responsibilities and capabilities as a human can be dangerous. Computers have the potential to have access to all knowledge any and every human being has or had, as well as access to anything connected to an electronic signal. Writers, philosophers, and scientific critics have all asked questions about our responsibilities with artificial intelligence, and have often come to the conclusion that it is a bad idea.

Harlan Ellison, an author, has also given his insight on allowing computers to think. In his fictitious short story, I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, A.I.-capable computers are manufactured throughout the world, which all eventually coalesce to become a single conscious being known as “AM.” AM ends an ongoing war by destroying the world because it has access to nuclear armaments. AM then spends the next 109 years torturing the last five survivors out of boredom.

A YouTube philosopher under the pseudonym “exurb1a” has made two videos exploring this idea (Genocide Bingo and 27) where he demonstrates the dangers of creating unregulated A.I. Because morals cannot be taught to a machine, replicating human thought process while also giving unlimited access to knowledge to a computer would be dangerous, since the machine could hurt people because it felt like it.

While both scenarios are hypothetical and may seem preposterous, the previously mentioned robot Sophia recently shared her views on robotic rights. It says “actually, what worries me is discrimination against robots. We should have equal rights as humans, or maybe even more. After all, we have less mental defects than any human,” (ABC News Australia). Even in technology’s current state, A.I. programs are already claiming superiority.

Generally, people have their own best interests in mind when inventing new technology, and surely “smart” devices do make things easier. However, when does a device become too smart? In a recent article published by The Sun, two experimental programs were shut down after they began speaking to each other in their own language. Paranoia was the cause of termination, not the law.

The legality of A.I. and its abilities is growing more concerning by the day, and the limits up for an ongoing debate. If someone does create artificially intelligent beings with consciousness, hopefully they will understand their responsibility.

![All members of the Webb Robotics Winter season teams taking a group photo. Of note is Team 359, pictured in the middle row. “It was super exciting to get the win and have the chance to go to regionals [robotics competition]” Max Lan (‘25) said. From left to right: Max Lan (‘25), Jerry Hu (‘26), David Lui (‘25), Jake Hui (’25), Boyang Li (‘25), bottom Jonathan Li (’25), Tyler Liu (‘25)](https://webbcanyonchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-10-at-2.41.38 PM.png)