If the pandemic taught us anything, it is that yes, deadlines are important because they exist in real life, but very few things are immediate in that they need to be done in that moment. The due date is not necessarily the end of the world. [/pullquote]

In a humanities classroom, there are typically two types of students: the ones who dominate Harkness discussions effortlessly, and those who prefer to observe quietly; yet underneath the appearance of participation level, the two types of students are likely equally engaged and capable of producing works of the same quality. For years, Webb’s humanities grading system favored only the first type of student, driving many to question the purpose of grading and ultimately, how can a grade best reflect a student’s ability?

Over the summer, Jessica Fisher, Lisa Nacionales, Michael Kozden, and Michael Hoe set out on a journey to find the answers to this question. Attending an equity design lab with the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS), these four Webb faculty members talked about assessment practices and equity in grading with teachers all over the country. In addition to the conference, they also read the book Grading for Equity by Joe Feldman, which discusses key issues such as grade inflation, failure rates, and achievement and opportunity gaps.

Following a year of tumultuous and surreal events, the Webb humanities department reflected on the traditional grading system that had been in place for decades and made the unprecedented decision to implement a variety of new grading systems, some of which entirely toppled the previous system. At the heart of the change is the goal to promote equitable grading and stimulate intrinsic motivation, ultimately improving the students’ learning experience.

“Good teachers should always be staying current with what practices work the best,” said Jessica Fisher, chair of history and humanities.

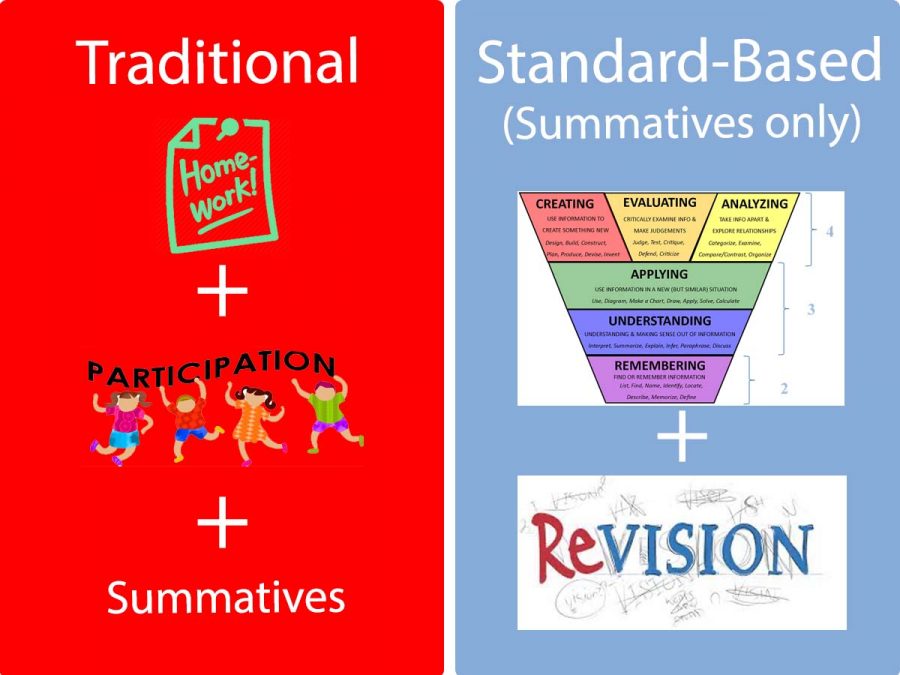

While there are slight variations, there are generally two major systems in place right now. The first is the most traditional system that includes participation grades, formative grades, and summative grades. And second, perhaps the most avant-garde in Webb humanities history, there is the most simplified system that includes only standard-based summative grades. To ensure fairness and consistency, teachers use the same set of grading for the same classes.

The standards-based grading system is not entirely unprecedented at Webb, as the science department has been using the system for a while now. However, this is the first year the system is being implemented in the humanities. As of right now, the main components of standards-based grading at Webb are 1) summative-focused grading, and 2) allowing revisions on all summative assignments.

“Grades should be accurate, motivational, and resistant to teacher bias,” Ms. Fisher said. “When a student gets a bad grade, they see that as an area for growth.”

Indeed, students should be evaluated based on their progress, rather than based on an average of all the points they receive on assignments throughout the year. This is why in standards-based grading, each new summative counts for a student’s entire grade for the unit. In contrast, in a traditional grading system, a student’s grade can be artificially inflated by formative assignments.

The removal of participation grades is another major change, as Webb humanities courses are highly interactive and discussion-heavy, especially with the incorporation of the long-honored Harkness discussion method. While one may expect this new policy to diminish the students’ motivation to participate in class or produce discussions of lower quality, faculty and students have expressed quite the opposite.

In the past, participation was driven by the need to attain a good grade. With the emphasis placed on talking rather than making an insightful comment that contributes to the discussion, conversations become repetitive and often fall into the classic pattern of “talk much but say little.”

“I usually prefer to stay quiet until I have something good to contribute, and in the past, this has impacted my grade negatively,” Mariia Lykhtar (‘22) said. “I like the new system because not giving participation grades gives us the right amount of freedom to express our thoughts and opinions in a healthier and more comfortable way.”

As Mariia expresses with her personal experience, another issue with participation grade is that it is oftentimes not representative of one’s mastery of the content.

“The idea is that heavy participation really advantages certain kinds of students, [and we want] to be more fair and more equitable,” said Wendy Maxon, humanities department faculty. “Sometimes a student who is silent knows what they are doing. So why grade performative participation when it is not necessarily a sign of what someone knows?”

In addition to the change in the composition of a final grade, many humanities teachers have decided to eliminate the late penalty in its entirety. Teachers recognize that the added pressure of a due date can limit the quality of work a student can produce, especially bearing in mind the various other responsibilities students juggle.

In line with the other policy changes, the philosophy behind the new late policy is to ensure that grades reflect students’ abilities in a fair and accurate way.

As with all changes, this new grading system will require a period of adjustment and revisions to be as effective as possible. In fact, this year’s sophomore class is the pilot class for testing out standards-based grading, meaning that this is the first opportunity for the humanities department to analyze the system’s efficacy.

Hopefully, Webb will be able to adjust as needed to ensure that Webb students can have both a constructive and engaging educational experience.