My parents often speak of education, of how it transforms lives and helps people dismantle stratification. Education has been the core of my dad’s story of self-making, and now it is becoming my own.

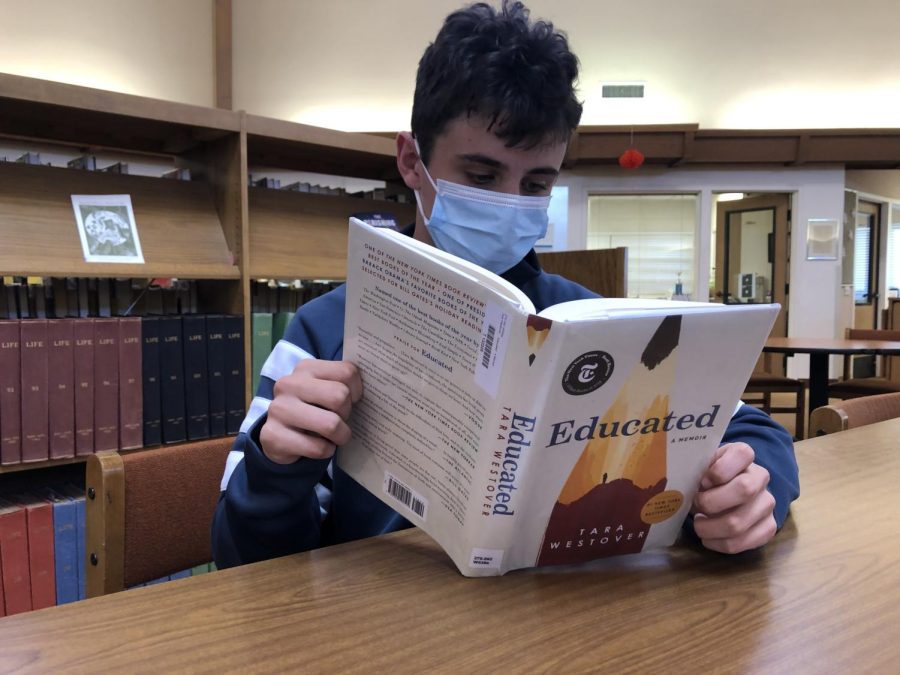

To Tara Westover, author of the memoir Educated, education renews her vision and awakens her awareness of the world, freeing her from the heavy weight of traditional constraints of womanhood imposed by her upbringing. Being educated allows her to break out of the silence of ignorance, to have a voice that resists. This transformation is Westover’s power of education.

When I traveled to rural villages in Guizhou with my mom and was left disheartened, troubled by immense discrepancies, fathoming the way out, all my mom talked about was education. At first, I did not understand her. It seemed to me that nothing could solve a problem so intricate.

But a part of me wanted to believe that my mom was right—that education, even if unable to immediately save us from all kinds of oppressions and injustices—can be powerful enough to at least give us the perspectives and ideas necessary to realize them. It saves us from the most helpless state that Tara Westover describes in her own book: remaining under exploitation, existing under false, alternative realities that justify injustices.

Often, the most oppressed are forced under persisting exploitations such that the oppressors strip them of all agencies, forging alternative realities that further oppression. This separation is where education comes into play. Like Tara Westover writes, “My life was narrated for me by others. Their voices were forceful, emphatic, absolute. It had never occurred to me that my voice might be as strong as theirs.”

What education means to her, similar to what it means to both of my parents who left their rural hometowns in pursuit of high school, college, and eventually doctorate degrees, is the possibility of navigating her own life with her own beliefs and ideals. It means being able to determine her own paths, not her parents, not her rural backgrounds, not those who diminish her self-worth. It is what Tara Westover calls the “custody of my own mind.”

She writes, “Everything I had worked for, all my years of study, had been to purchase for myself this one privilege: to see and experience more truths than those given to me by my father, and to use those truths to construct my own mind. I had come to believe that the ability to evaluate many ideas, many histories, many points of view, was at the heart of what it means to self-create.”

Westover makes the story personal, not just to me, but to many whose lives change because of education. Education saves her from seeing herself as worthless, but she begins to break out of what her own family makes of her, as she writes, “Of the nature of women, nothing final can be known. Never had I found such comfort in a void, in the black absence of knowledge. It seemed to say: whatever you are, you are woman.”

I love the crisp, rhythmic title of the book. But it can also be misleading. More than a book glorifying the unfathomable power of education to transform, the book is about self-empowerment, resistance, using new visions to reevaluate the past. It is about traumas, reconciliations, and the process, possibilities, and impossibilities of healing. It is about forgiving, and it is also about remembering. It shows that education is not just attending school, but more importantly, learning to challenge what we have taken for granted. More than memorizing facts, education is about learning and thinking independence.

Many people call the book “inspirational” and applaud the author’s grit and resilience, admiring how education can transform someone so wholly. But we should not reduce the memoir into a simple legend of education transforming someone from savagery, conservatism, alienation to educated and successful.

Clearly, the story is more complicated. The story, seemingly so unblemished, falls too perfectly under the trope of the “American dream.” But it is the opposite. Throughout the book, Westover challenges such simplification, showing that beyond her success, there have been losses, sadness, confusion, and unhealed wounds along the way. She understands her transformation encompasses “falsity” and “betrayal.” She calls it education but knows that it is more than that. Beyond escaping ignorance, she has found self-empowerment and empathy through education.

When I read her story, amazed, I often think about the many other people with similar experiences, who have been hurt, abused, silenced but remain in the abyss of silence. Whose stories, equally or even more horrifying, remain untold. Not because they do not exist, but because they lack the channel of telling them—whether it be self-doubt or ignorance of their own abuse—all stemming from a lack of the opportunity of being educated. I think about their stories, their struggles, and what is left to be known.

Tara Westover tells her own story. We can call it legend; we can call it a myth. Whatever it may be, it is a potent force speaking against abuses and silences. But it is only one of many, among millions and billions. Many of these stories are still trapped. How to get them out? I do not know the exact answer. All I know is, transformation is difficult, and education is even harder. But from what I have seen from my family and Tara’s story, I find myself returning to my mom’s murmuring even after we left the villages: education.