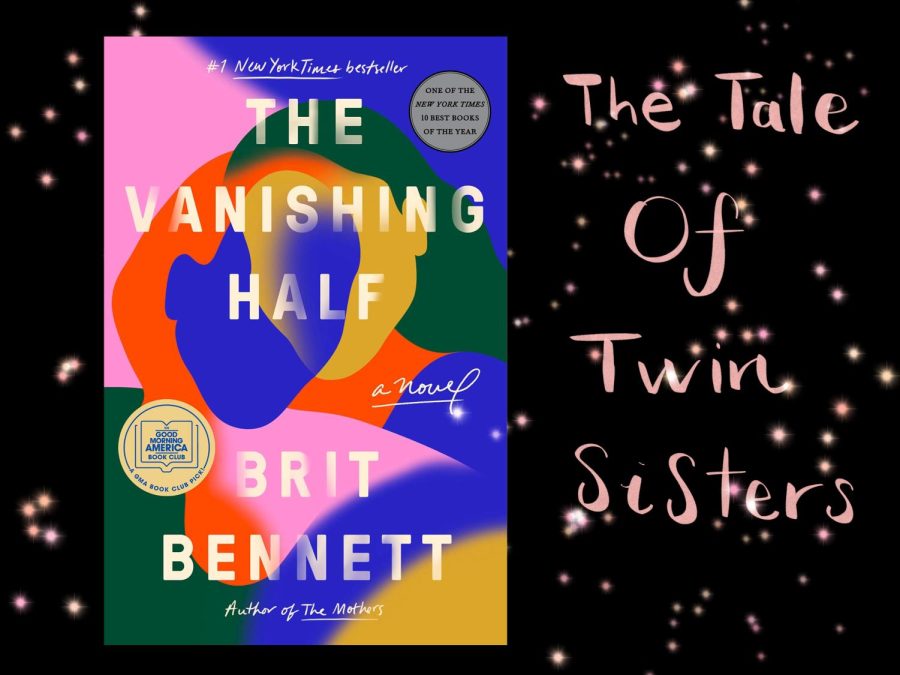

Identical twin sisters. One integrating into privileged White society, and the other marrying the darkest man she could find. In The Vanishing Half by Britt Bennett, Stella and Desiree thought their fates would never cross again, but a chance encounter between their daughters once again reunites their stories.

The compelling, creative plot first drew me to the novel. As I turned the pages, expecting to find a cliché tale about family drama, I found myself instantly hooked by the literary flair, breathtaking plot twists, and delightful insights into the worlds of Black and White—and what it means to be in between.

I was intrigued and puzzled by Mallard, a town that is filled with people of color, but somehow still finds a way to project racial discrimination toward others. I scraped my mind to understand how victims that suffer from grotesque, dehumanizing systemic oppression amplify that mindset to inflict more harm on others. The author takes this book as an opportunity to touch on the overlooked topic of colorism. Just like the typical American middle class that blames the lower class for wasting all their taxes on welfare, the lighter skinned residents at Mallard detest the sight of Blackness, a living reminder of the inferior lives they cannot escape. They feel unfairly subjugated to the racial segregation despite many of them being White-passing, and in turn, project that bitterness to the Black people around them.

When in bed with her boyfriend, Jude, Desiree’s daughter, says, “In the dark, you could never be too black. In the dark, everyone was the same color.” Her wistful desire for equality no doubt stems from her traumatizing childhood in Mallard, where no one would befriend her due to her dark features, but it also reveals her innate insecurities. The bullying she endured as a child led her to internalize the belief that no one would truly love her because of her skin. This is not merely a fictional tale, but something that still haunts our society today. Like every means of social control, colorism has its costs, and women have been made to pay an unequal fraction of the price.

When Stella passes onto her life as a white woman, she recalled not realizing “how long it takes to become somebody else, or how lonely it can be living in a world not meant for you [her].” Her experience is vivid proof of the need for belonging, a tangible struggle that almost all of us go through. Whether it’s the color of one’s skin, culture, background, or socio-economic status, one facet of identity always plays a dominant role in helping one find belonging. Stella embodies this principle, as her act of abandoning her family and cultural heritage left scarring voids in her life, though practical in the short term. Her seemingly perfect life is founded on colossal lies, depriving her of the opportunity to even show her true self to her daughter.

One part of Kennedy’s childhood struck me the most. She was playing with Loretta’s daughter, the next-door neighbor who had just moved in, and witnessing this, Stella stormed in to prevent her daughter from playing with a Black girl. When she tries to apologize afterwards, Loretta says, “Your guilt can’t do nothin for me, honey. You want to go feel good about feelin bad, you can go on and do it right across the street.” Her statement illuminated the many performative apologies that we see daily: ones made to ease the perpetrator’s guilt, not sooth the victim.

In the end, to automatically hate and fear anything or anyone different from ourselves and to want to feel smarter and worthier than an entire race are two of the least admirable and most regrettable aspects of society that unfortunately still linger today. However radical the changes that current government officials made to policies, they did little to modify or improve the most neurotic anxieties and destructive biases against people of color.