As course selection season nears, you might find yourself scrolling through the course catalog, browsing the over ten different science class offerings. Your final course selection decision is a balancing act of many different factors: The difficulty of the class, its field of science, the prerequisites, and department recommendation. Would the gender ratio of each class ever make its way onto that list?

Over past years, Webb has consistently seen a trend of only a small percentage of female students opting for math-based, higher level physical science STEM classes. The most striking example is AP Physics C, with only three VWS students enrolled in a class of 18 this year.

Between 2018 to 2022, the gender ratio of physical sciences (Advanced Studies AP Physics C and Advanced Studies Experimental Physics) at Webb has been 68 :32 male to female while the gender ratio in computer science and advanced math classes is 60:40.

These statistics are worrying. Professional STEM fields are already known to be heavily male dominated, with men in roughly two thirds of all STEM based employment. With fewer female students taking classes in physical science at the high school level, the cycle of gender discrimination in STEM continues to be perpetuated through levels of job development and Webb’s education system.

Diversity in STEM is particularly important, because STEM is essential in shaping the direction of the future as it is involved in nearly every profession. Diverse workplaces pave the way for more innovation and fairer representation.

With all this said, why aren’t VWS students taking harder STEM classes?

Many physical science classes require prerequisites in math, demonstrating that the women in STEM issue may track back to before high school begins. AP Physics C requires AP Calculus AB as a prerequisite, and Experimental Physics requires Integrated Math 2.

Another factor is that women are discouraged from choosing classes when they know they are going to be the minority. Classes like physics are outweighed by other social and life sciences that lack the discomfort in these imbalanced environments.

“It feels like I must be better [than the males in the class] because I must prove that I’m as good as them; I deserve to be there too,” said Aiperi Bush (‘24), a VWS student who took AP Physics C last year. “Even if there’s a few other girls there, it does still feel overwhelming; at least to me, you can feel that gender divide.”

In addition to quantitative factors, preexisting gender norms, societal expectations, and cultural and family backgrounds also play a crucial part in these results. The most significant reason discouraging VWS students from taking these classes is not the lack of support from the school but rather the overall experience of women in the US when it comes to STEM.

Women are taught to feel unwelcomed in STEM classes, to fear failure when accepted into these spaces, and constantly told that in the workforce, they must work twice as hard to stand out and prove themselves.

Another factor lies in the gender stereotypes associated with different job options. Fields like environmental science and biology might be more popular with women because they are subjects perceived as more nurturing or caring, whereas physics and math are more associated with logic and facts.

Even teachers have difficulty facing and navigating this phenomenon, as there is only so much one can do to reverse the entrenched cultural programming.

“Whether you’re talking about an individual teacher or an individual school, you’re trying to overcome a lot of built in expectations about what it means to be in that class and the kind of pressures that will be on a person.” said Andrew Hamilton, science department faculty and AP Physics teacher. “I can’t imagine what it’d be like to walk into a classroom and not just think ‘am I going to do well.’”

A step Webb has taken towards encouraging female students in physical sciences is the STEP-UP program. For the advanced studies classes, the teachers do a presentation on awareness and female representation at Webb. IPC students receive a presentation on possible careers for physics majors, highlighting influential female physicists and encouraging VWS students to continue with physical sciences.

Two students expressed contrasting thoughts when interviewed about the STEP-UP program.

“When you just do science, you don’t really get to look at what’s surrounding the science,” said Sehoon Kang (‘24), a WSC student who took AP Physics C, “In our classes, we don’t really care whether you’re a girl or not, because we’re all inclined students. I’ve never really thought about it that way.”

But while intentions of classmates may be one thing, the actual experience of females in these classes may be different.

“The conversation really devolved,” Aiperi said. “We ended up getting a couple of guys just denying that sexism existed, essentially. It’s scary because I would say I’m normally outspoken, but when there’s [so] many guys talking over you, it’s hard not to shut down.”

The STEP-UP program sparks valuable conversations in the classroom, with a goal to build confidence in girls, enhance awareness in male students, and brainstorm solutions to the gender divide for further change. However, even during moments of advocacy and encouragement for women in STEM, difficult conversation arise.

“Even if it’s a student who wasn’t really invested in the conversation at the time, maybe next time they’ll be more open to it,” Mr. Hamilton said.

Even though these are small steps, it is worth acknowledging that they contribute to long term change.

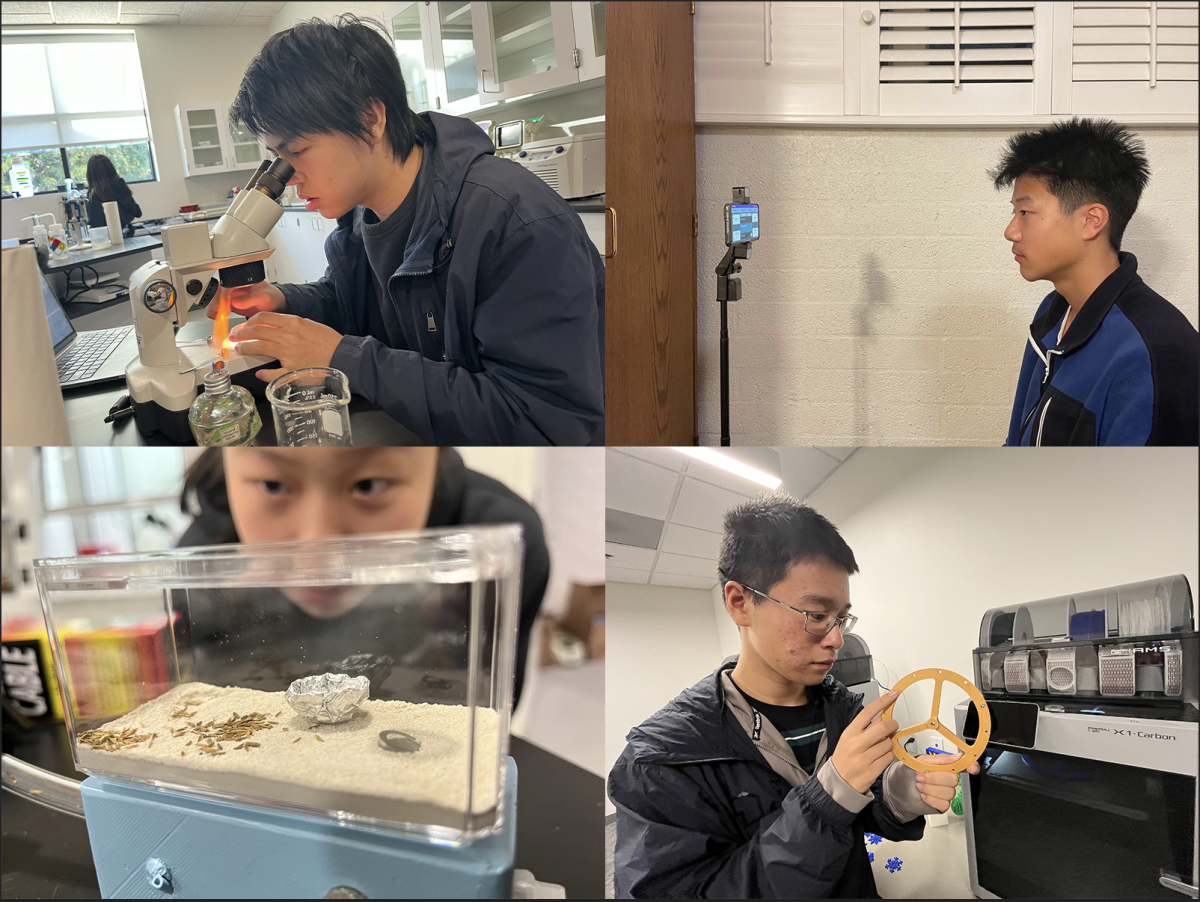

Although the STEP-UP program is a meaningful step towards long-term change, the status quo seems unlikely to shift. Despite an even split between genders in the science department faculty overall, all physical science teachers identify as male.

“It can be discouraging because especially when you look at the labs, they will be heavily male dominated and that can be a little off-putting and intimidating for a VWS student,” said Billie Guerrero, science department faculty. “How are we going to make sure that the girls are getting their space to be comfortable, to be able to flourish in those classes?”

Webb’s next step to promote women in STEM should be increasing female role models in the field of physical science.

“It helps to see teachers who are also women, and to see that they know what they’re doing,”Aiperi said. “When they’re women, it makes you feel more comfortable.”

There is a lot that Webbies cannot control, such as cultural programming, historical patterns, and family influences. However, encouraging VWS students to pursue STEM should be a priority.

![All members of the Webb Robotics Winter season teams taking a group photo. Of note is Team 359, pictured in the middle row. “It was super exciting to get the win and have the chance to go to regionals [robotics competition]” Max Lan (‘25) said. From left to right: Max Lan (‘25), Jerry Hu (‘26), David Lui (‘25), Jake Hui (’25), Boyang Li (‘25), bottom Jonathan Li (’25), Tyler Liu (‘25)](https://webbcanyonchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-10-at-2.41.38 PM.png)