All clear! Amazing! Excellent!

Do these commendations make you feel good? These celebratory messages light up your screen as you play Block Blast, the mobile puzzle game slowly taking over the Webb community. Whether it is studying in the library during X-block in the library, procrastinating on homework deep into the night, or even pulling out a phone in the middle of class, students are found swiping on their phone, aiming for a new high score on Block Blast.

Inspired by Tetris, the game challenges players to drag and drop differently shaped blocks onto an 8×8 grid, clearing full rows and columns to rack up points. The simple mechanics make it easy to pick up but have a layer of strategic depth that feels rewarding, keeping players coming back for more.

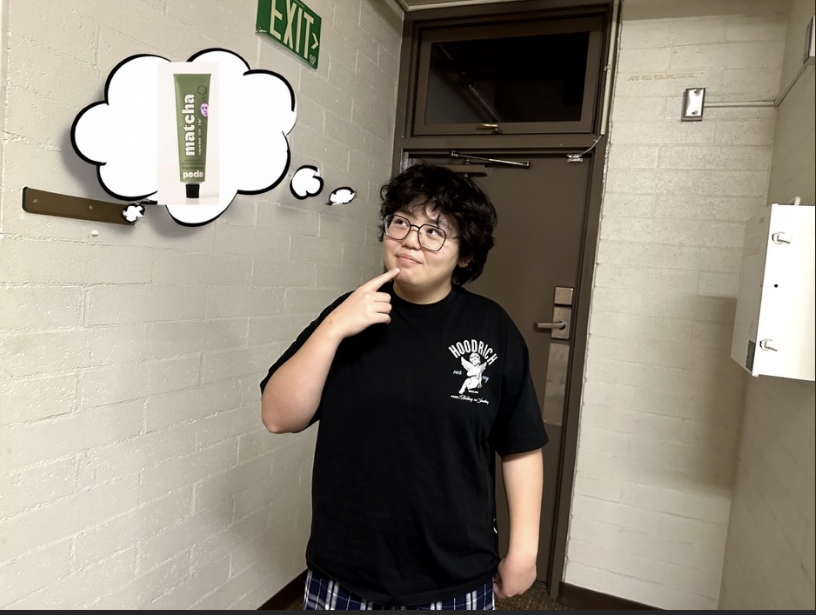

“I downloaded it because a friend was playing on her phone and then wanted to try it too,” Maya Chin (‘26) said. “The bright colors and the way it makes your phone vibrate when you get a full clear is very satisfying. When I get a combo, I feel great pride.”

Block Blast’s addicting nature lies in the dopamine rush of the game. The combination of bright colors, vibrations, and the rewarding feeling of working toward a high score makes it captivating, despite the simplicity of the game. Additionally, there is an “adventure mode” that challenges players to finish 100 levels in a week, creating a sense of immediacy that motivates players to play in the moment.

“With Instagram reels, you have to watch it for 10 seconds to a one minute to get a dopamine boost,” Aaron Yang (‘25) said. “Block Blast is even better. Every single time you clear a line, which you can get in a couple seconds if you’re good, it’s dopamine. It’s basically Instagram reels on steroids and more efficient.”

You could play Block Blast forever: the game always gives you blocks that can fit into the grid, so if you think hard enough, you can always advance to the next step. This mechanic mimics the never-ending scroll of social media that we all know, making it easier to take up more time.

As Block Blast continues to attract players across campus, its irresistible appeal is becoming more noticeable — sometimes making it harder to stay focused.

“I can’t even write for an hour before I get the urge to play block blast,” Maya said. “Instead of counting sheep at night, I see the blocks falling into place, and I see myself doing an all clear or a four-way combo and then an all clear. It just feels really good.”

On a further note, some claim that the experience of playing Block Blast itself is not even enjoyable, but rather addicting and distracting to the academic Webb experience.

“It’s just a waste of time,” Aaron said. “I don’t even enjoy playing it; I just want to play it. In fact, I’ve incorporated the Pomodoro method into my studies after discovering Block Blast: 5 minutes of work followed by a 20-minute Block Blast break.”

Block Blast is the latest fad captivating Webb students — just as many mobile games such as Brawl Stars, League of Legends, or Clash of Clans have in the past. It is almost comical how so many students are addicted to such a simple game — this addiction is prevalent nationwide.

Although there is little research done on the science behind Block Blast and what makes it addictive, many student journalists from different schools across the country such as Phillips Exeter, Berkeley High School, Ladue High School, and more have reported similar surges in popularity within their respective school communities from late 2024 to early 2025.

It is no secret that mobile gaming is one of the many distractions that makes its way into our generation of students. At a time where the world is faster paced, social media platforms are even more accessible and normalized.

Short form content such as TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Instagram Reels continue to feed into the demand for instant gratification. The term “doomscrolling,” or spending an excessive amount of time absorbing information from short form content, has been popularized. Similarly, “brain rot” is an internet term that refers to low-quality content. It has negative effects on mental and cognitive functioning but is easy to consume, leading to content overconsumption or deterioration.

“Reels are like tiny grains of sand,” Aaron said. “Individually, they mean nothing. No one pays true attention to a singular reel, no matter how unique or interesting or funny it is. But altogether, reels are like a beach. They make up a beautiful experience but can waste away your whole day.”

Content such as Instagram reels or TikToks are so short that users are not absorbing much meaning from it, as opposed to material that requires more attention, such as reading a book or watching a video essay. Yet, this content is easy to digest, which draws users back yearning for another rush of dopamine at even faster of pace. This constant cycle of instant gratification makes it increasingly difficult for users to engage with longer, more thought-provoking content. Over time, this developing habit reduces the attention span of users.

Whether it is social media, mobile games such as Block Blast, or any other addicting distraction, they capitalize off the same properties: a need for entertainment, context collapse, dopamine, and instant gratification.

In Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman, written in 1985 even before the rise of technology, he argues that modern society is inevitably controlled by entertainment and pleasure. While print culture inspired critical thinking and discourse, television prioritizes amusement, and the visual appeal of the media we consume becomes more important. Postman’s arguments have only been amplified with the rise of short-form content. He mentions that the seriousness of topics such as religion and politics are reduced into forms of entertainment.

“People need something that is gripping and will get their attention really fast without taking too much time,” said Olivia Silva, humanities department Faculty and Advanced Studies Literature and the Machine teacher. “Entertainment takes place not just in television, but in politics, education, and government now.”

In context with today’s world, Postman’s arguments still remain relevant. Elements such as color, sound, and appearance in media are what attract us. At first, the diverse range of content in our digital feeds, from TikTok dances to relatable commentary, appears to enhance our lives with knowledge and entertainment. However, over time, a more significant problem lies beneath this apparent variety: the loss of context.

From Brat Summer to the Ocean Gate submersible implosion, political debates and world issues are reduced to memes and soundbites, as audiences do not need a full understanding of a situation to comment on it. Since users are absorbing content that does not need context, it is likely that they will not fully remember or understand what they are viewing. Similarly, a game like Block Blast does not require previous knowledge to immerse a user in its gameplay — it is a form of escapism that only provides pleasure, using visual elements such as bright colors and positive messaging to create dopamine.

“It’s easy to see headlines and find irony in it or turn it into a joke, as people are more accepting of news that brings laughter in a world filled with so much uncertainty,” Isaac Nicolosi (‘25) said. “Misinformation spreads as not a lot of people fully put in the effort to understand the news or research the historical context behind an issue.”

Companies capitalize on our addiction. In 1971, psychologist and economist Herbert A. Simon wrote about the concept of the attention economy, stating that “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” For every minute we give our attention to a mobile game, a social media post, or a YouTube video, companies hurl advertisements at us, collecting data on our interests and using it to keep us on their platform for longer.

Unknowingly, we become products of this business model that profits on our attention, yet it is so ingrained in our daily lives. The attention economy, which views human attention as a valuable resource in an era of abundant information, has influenced the development of teenagers’ brains, leading to shifts in their lifestyles.

Inevitably, the commercialization of our attention and the easy access to dopamine influence our education — the way we learn and hold information, how well we concentrate, and how we engage with complicated ideas that require background context.

“Teachers have said repeatedly that we do less content than we ever did before, and that is ongoing,” said Melanie Bauman, Director of Wellness. “The ability to do work has changed. It is definitely correlated to the pandemic and is certainly impacted by the lower attention spans. We’ve been seeing this [students lacking executive functioning skills] since the rise of MTV, the snippet kind of engagement that people are looking for.”

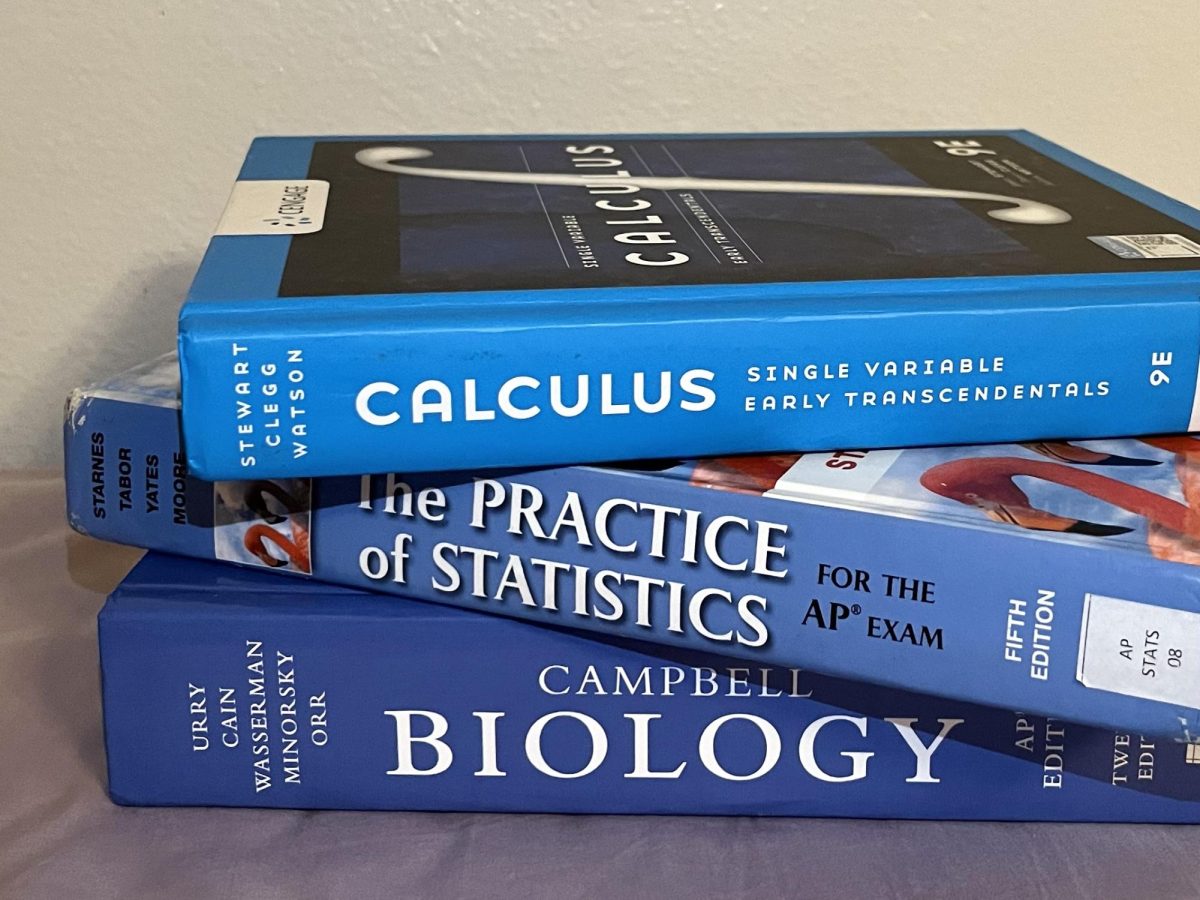

In the humanities courses, one of the biggest impacts of having shorter attention spans is the ability to immerse oneself in a long reading or even complete long readings. Sustained reading is an important skill to have, as long-form content builds skills such as building connections and seeing from other perspectives, in addition to understanding the complex content presented in the specific reading that is assigned.

“When I started teaching here, I was regularly assigning 60 to 70 pages of reading in most of my classes and students were fine with it,” said Elizabeth Cantwell, chair of the humanities department who has taught at Webb for more than 12 years. “I just assigned 55 pages of a pretty easy book in my Advanced Studies class, and my students felt like they were going to die.”

To adapt to the rise of media and lowering attention spans, Dr. Cantwell has decreased homework assignments over the years. She has ensured that educational standards remain high by focusing more on depth rather than covering a wide range of topics, without sacrificing skill development. However, the lack of concentration and executive functioning skills with students have created other issues in the classroom.

“We have seen more increased issues with collaboration in group projects, and my guess is that that probably has to do with the [decreasing] time management and executive functioning skills,” Dr. Cantwell said. “When different students in a group might be procrastinating a group task, the group project starts to feel like it’s going off the rails. A student will get super stressed, everyone gets anxious, and people end up fighting.”

During class, digital distractions like phones and laptops have also increased, forcing teachers to adopt stricter classroom norms.

“When students sit down in class, I noticed a lot of them immediately open up their laptops when I don’t mention laptops or give permission,” Ms. Silva said. “Oftentimes, I say that we don’t need our laptops right now, and I still see a lot of people use their phone under the desk or inside their book.”

From a student’s perspective, digital devices can serve as both a distraction and a coping mechanism for staying engaged during long lectures in class.

“I play Tetris in class because I have a horrible attention span, and my fingers play the game through muscle memory, so I often play the game while teachers are talking.” Frannie Hinch (‘25) said. “Technically, brains can’t multitask, so I zone out while people are talking unless I am really invested in the conversation.”

Webb has tried to combat this reliance by making more tech-free spaces and initiatives, such as banning phones in the dining hall and implementing Reboot November. However, Webb students did not pass the community challenge.

Many students struggle to engage with long-form content, finding it not entertaining enough compared to the constant stimulation of digital media. Another example of the demand for entertainment is the Instagram Reels or TikTok videos that combine TV clips or story time with gameplay from Subway Surfers or Minecraft Parkour, designed to capture and hold users’ attention. Jose Munos-Lopez, math department faculty, attempted to teach a lesson in AP Stats using a similar format.

“As Gen Z, I understand how addictive our phones can be and how the endless scrolling can really take up time,” Mr. Munoz-Lopez said. “I tried using the brain rot in the background to teach, but right now, I do not know if it works. I have to try to come up with good scripts for it, but I just think it’s funny. I don’t know if it’s actually useful yet, but maybe in the future.”

It is clear that students find distractions due to lack of concentration, but are also addicted to a dopamine rush, creating a need to be constantly entertained.

The lower attention spans and concentration levels are also impacting STEM subjects. As math is a subject that requires building on background context, many are struggling to progress in math. The pandemic’s shift to online education has also contributed to this.

These trends at happening at Webb are also reflected across the nation. USA Today has revealed that children’s math and reading levels have decreased, and less children read for pleasure compared to the past.

It may be a temporary mobile game fad, but Block Blast’s popularity at Webb and beyond reflects how a desire for dopamine and entertainment has rewired our brains and daily habits. If Block Blast is “Instagram reels on steroids,” what is next? Will we ever reclaim our ability to focus?

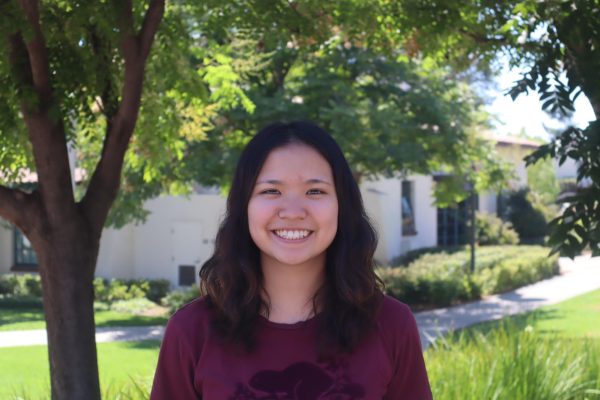

![Maya Chin (‘26) plays Block Blast on her phone during her free block in Stockdale Community Center. Block Blast is a mobile game similar to Tetris and has two game modes. "I think a lot of people play [Block Blast], but I don't know how many people are willing to admit it,” Maya said. “Since I’ve downloaded it and brought it up to other people, I’ve seen them also download and play it. I’ve seen some crazy high scores which are not healthy; they probably spent at least 3 hours trying to get it.”](https://webbcanyonchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_3360-1200x900.jpg)